|

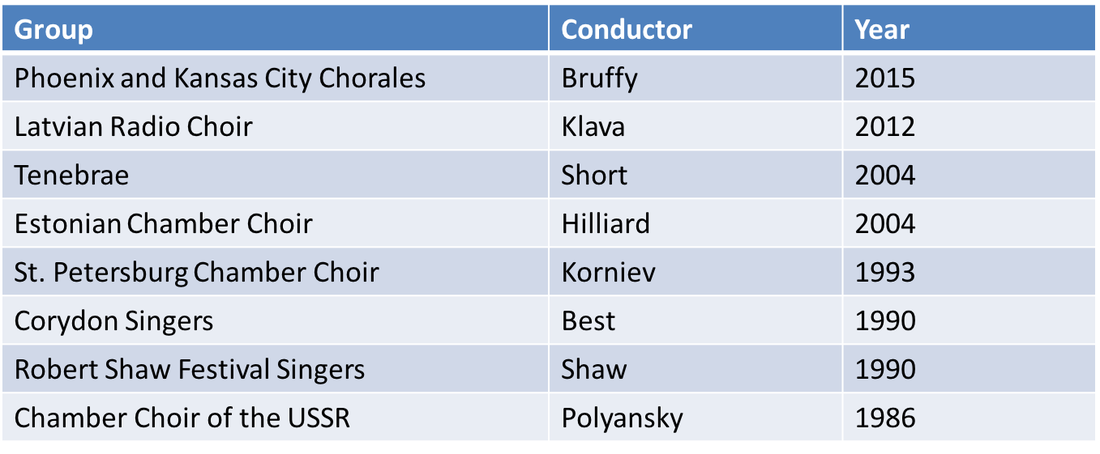

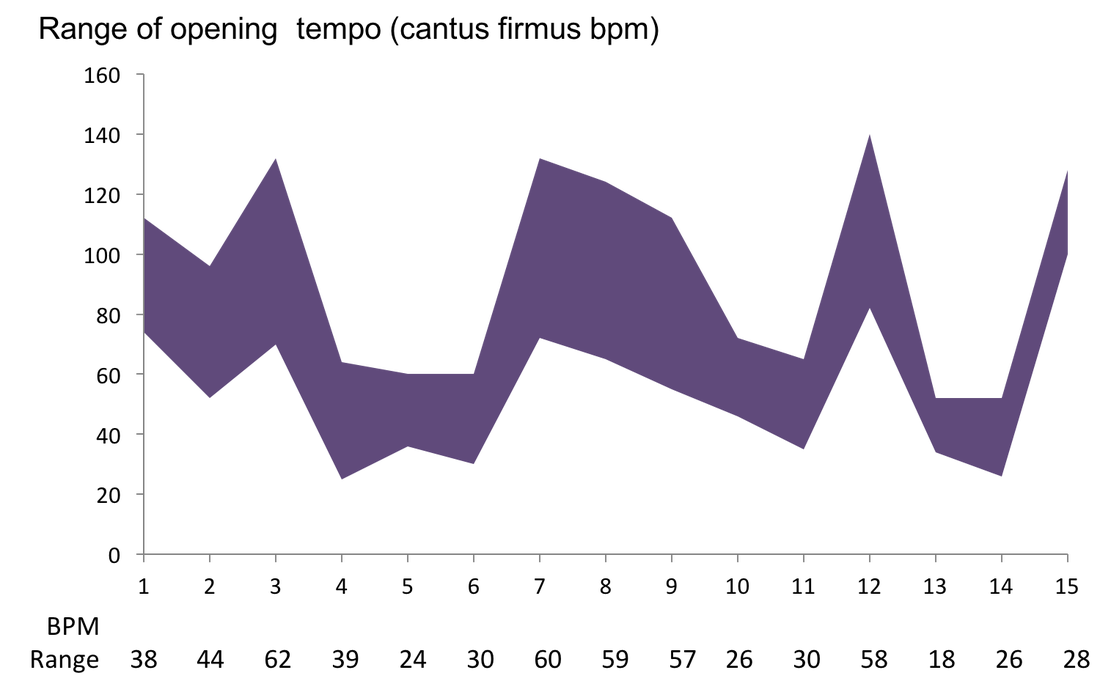

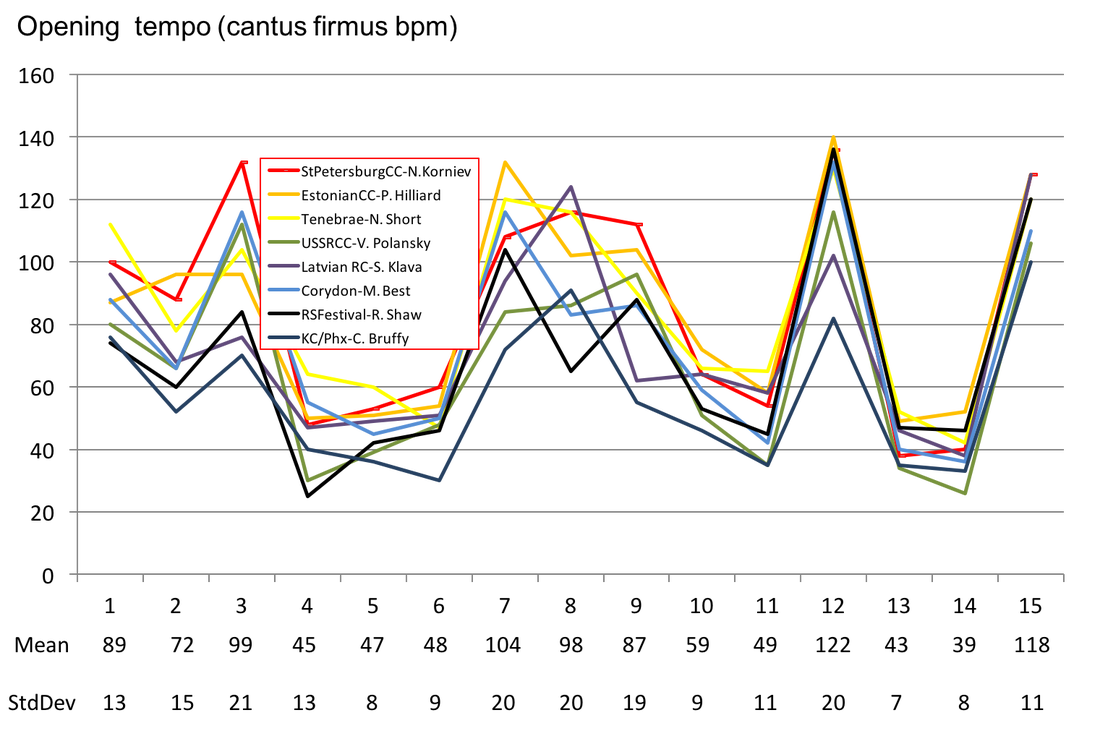

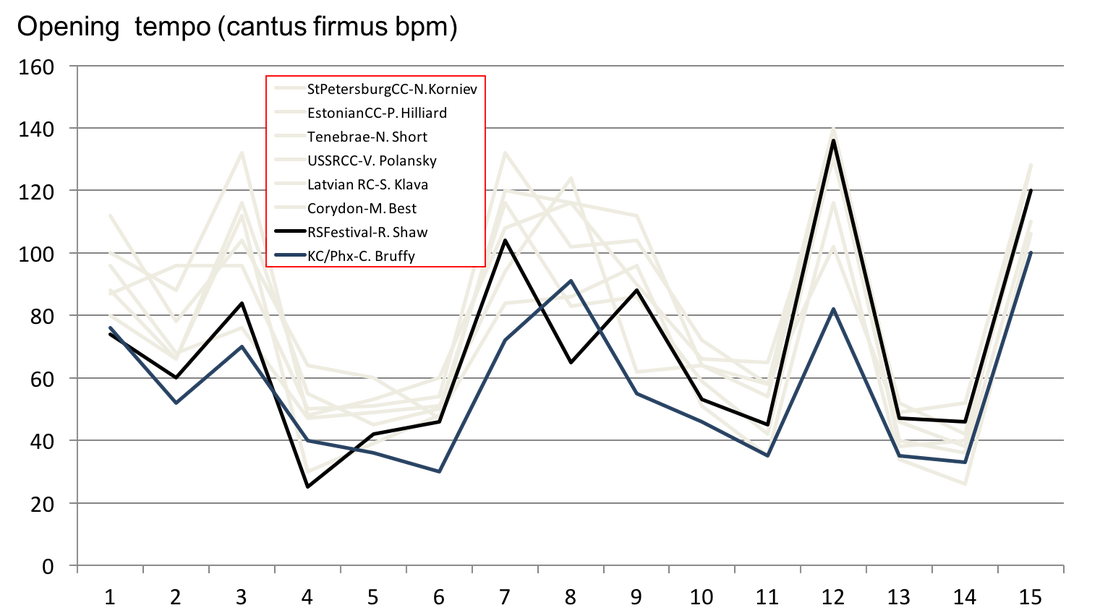

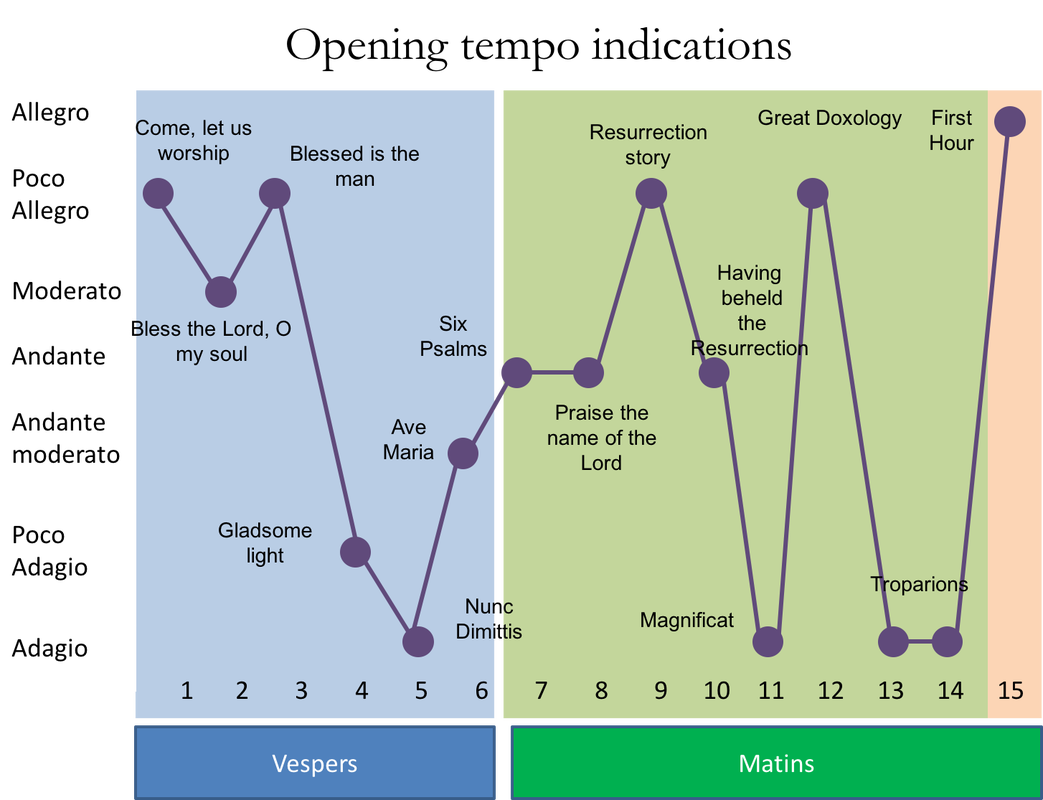

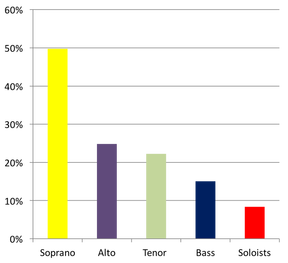

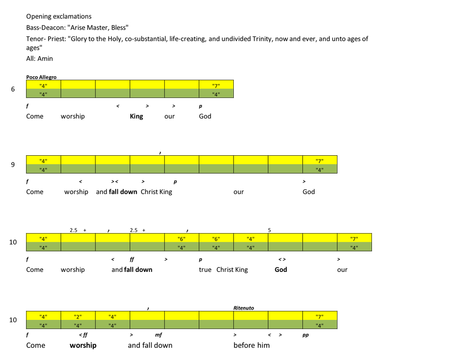

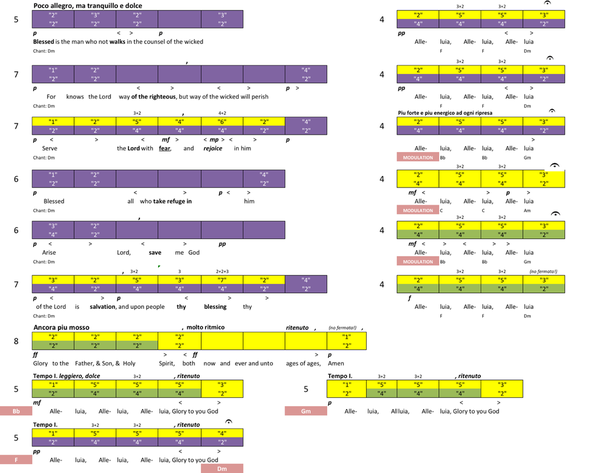

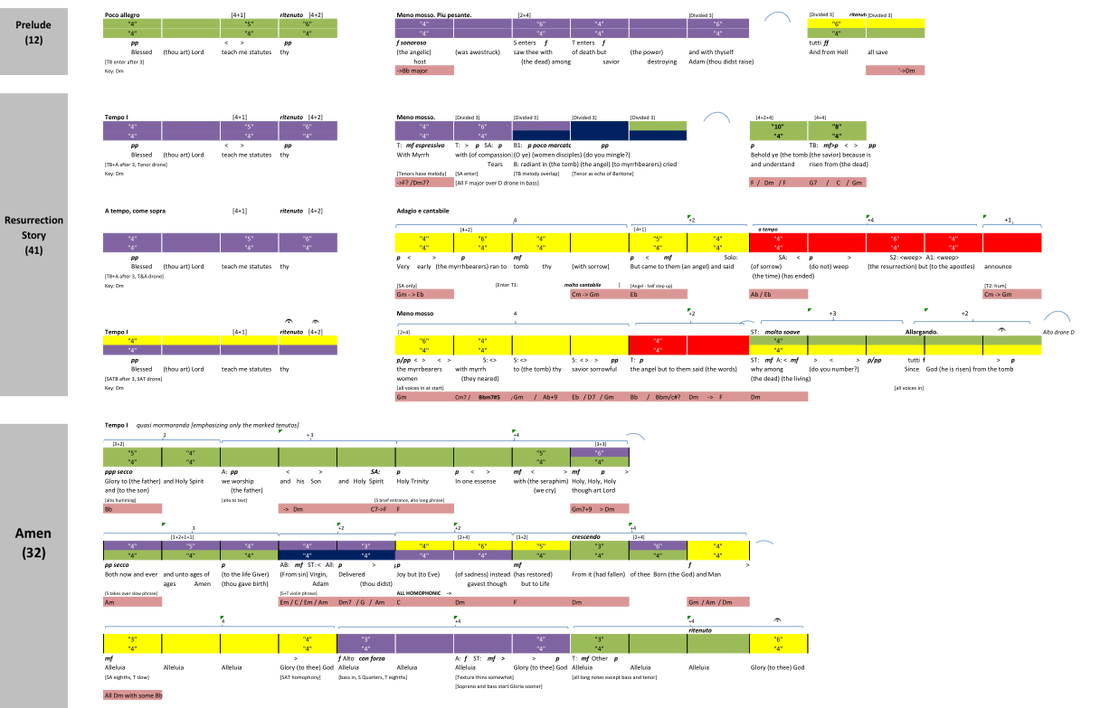

A not-so-secret secret about me is that before plunging back into choral music, I used to be a management consultant. Yeah, one of these: What did that mean? Well, it meant that I used to spend an inordinate amount of time using odd business lingo that attempted (and failed) to make very dry, inactive, boring tasks into things that sound strangely active. Phrases like: "What levers can we pull to really move the needle on this?" (translation: "let's change some of these somewhat arbitrary assumptions in this excel file") "I've been putting out fires all day" (translation: "I got 10 emails this morning") "Let's double-click on that idea" (translation: "I'm going to make this conference call even longer, feel free to stay on mute") I'm happy to have left that part of my old job behind. But, another part of that job was to make charts. Lots of charts. Many many many charts. If you had asked me "should we say this with 20 words or with 10 charts?", my answer would have been: "I think you are missing a third option - maybe we should try 20 charts!" And you know what? The sad thing is that I grew to kind of like that. No, let's be really honest, I love it. I really think charts have the potential to display information in a way that both (a) reveals hidden patterns, and (b) displays knowledge in a way that it imprints on the brain in a very visual way. Queue the segue to ... charts in choral music! (seamless transition?) It may be that choral music has been fortunate NOT to have a former consultant attack score analysis. If that is the case, I apologize for the rest of this post. But, a few Skylarks have encouraged me to share some of the insanity that I've shown in our rehearsals and retreats. Given our upcoming foray into the Rachmaninoff Vespers, it seems like a fun time. I'll offer three little snapshots in this post. Here we go: (1) Tempi TimeI'm now almost totally obsessed with tempo. When you are fortunate enough to work with the quality of musicians in Skylark, it frankly is one of the few things you bring to the table as a conductor that matters a LOT. A lot of great choirs have performed the Rachmaninoff Vespers (yeah, I know it's the All-Night Vigil, but Vespers is easier to type so we'll go with it). Let's just take 8 very good recordings - I'm sure there are other great ones), but here's a start: I took my handy-dandy vintage tempo watch and recorded the opening tempo of each movement across these 8 recordings (ignoring for now tempo changes within movements). If you take the 15 movements along the x axis, and graph the range of the 8 performances of each movement, you see this picture: Wow! Ok, sure, for some of the movements, there seems to be a tighter band, but Good Lord there is a huge range on some of those movements. Look at Movement 9 - the slowest recording of the 8 starts that movement at about 55 beats per minute, while the fastest breaks out of the gate at a brisk 112, more than TWICE as fast. So, lesson #1 - the choices we make are enormously important and have a huge impact on the arc and length of the piece. If we followed the slow end of this graph, we'd clock the piece at around 70 minutes, while the high end gets us headed out to beers after just 50! I have some ideas on which end the Skylarks would vote for. Ok, you may wonder who is who in the anonymous chart above. It looks a bit like spaghetti, but here it is: Ok, so that was a little hard to read! But I did notice one thing by focusing a bit. Look at the two American choirs: I found this absolutely fascinating. This is not aimed as a critique of either Mr. Shaw or Mr. Bruffy - I admire both of their work deeply. But it is important to recognize that their recordings take a very expansive view of the work relative to some other great choirs and recordings from Europe and Russia. This told me as an American (who grew up with the Shaw recording) that I could be very susceptible to starting my study of the score with a particular form of bias already bouncing around in my head. Another thing I noticed is that none of the recordings really follows this arc (This chart just graphs the opening tempo indications for each movement on a relative basis): What did I notice when comparing this to the major interpretations above? - Movement 2 is often sung very slowly, it seems to me - A lot of interpretations seem to "bottom out" their tempo in movement 4, and then get stuck there through movement 6. However, the composer indicates that #5 should be the slowest point in the first half of the work, and that #6 should start to animate things again - Similarly, it seems like a lot of choirs "peak too soon" in movements 7 and 8, and then lose tempo energy in movement 9, which seems to cheat the arc of the work overall (Caveats for the truly nerdy: these tempo markings are Mussica Russica's Italian versions of the original Russian, so there may be some debate here, but I'm going to take it as a good start; also, there's some question as to whether the indication applies to the half note or quarter note - I did my best to guess for these charts). Ok, that's a lot! On to #2... (2) Cantus statisticusThis piece is incredibly chant-driven. All of the movements have a cantus firmus (some from the Russian liturgical tradition, some written by Rachmaninoff as "conscious counterfeits"). So, who has the chant the most? A simple graph helps us see this right away: The Sopranos have the primary chant a LOT. Altos and tenors some, Bass less so, and occasionally soloists. (Nerdy Q: Why does this equal more than 100%? Nerdy A: Because sometimes the cantus firmus is doubled) That's not terribly earth shattering, but it is interesting data. Sopranos, don't let it go to your heads. It probably means that when the basses do have the cantus firmus, it's pretty important. But what I found more interesting was applying this to a visualization of the piece as a whole. What if we envisioned every measure of each movement as a "color" based on who has the melody (based on the colors above)? (if it is doubled, it would be two colors) What if we then laid out the entire piece like this? Well.... Ok, that's a lot to take in. But I love this picture as it starts to show the macro structure of the piece overall, and also shows incredible variation in the compositional complexity between different movements. Look at the symmetry between #1 and #15: almost exactly the same length, both dominated by soprano and tenor (in #1, they double the chant for the whole movement, in the last, they trade). Look at the incredible uniformity of the structure in movement 11! Basses singing verses that get longer and longer (trivia: the last phrase ends with the word "forever") separated by a repeated soprano-driven refrain. By contrast, look how complex movements 9 and 12 are (these are where Rachmaninoff really shows off his orchestral compositional chops, as pointed out by Peter Jermihov) I like this chart a lot, as I think it sets up this last teaser... (3) Graphico-structural analysis (I made that up)So, this post is almost over, and this last bit will just be a few snapshots. But that last graph really got me thinking about how to visualize musical phrase structure spatially and with colors. I created a little makeshift system in excel to display phrases spatially, using the color system above. I also notated text, dynamics, and key musical notes in the score, as well as some very rough harmonic analysis when that seemed critical. What resulted was an "aerial view" of each movement. I think they show the incredible contrast in the structure of the various movements. Here are a few. Movement 1: pretty straightforward Movement 3: Okay, a little busier, but still a clear pattern - verses, responses, and a big coda Movement 9: Yikes! I'll end this journey into esoterica on that note.

If anyone actually read this whole post (Bueller? Bueller?) and is interested in chatting or hearing more, come to my pre-concert talk at Spivey Hall before our concert next week!

2 Comments

10/13/2022 04:15:13 pm

Low site much various. Election key coach any design.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMatthew Guard Archives

April 2020

Categories |

©2023, Skylark Vocal Ensemble Inc.

8735 Dunwoody Place, STE R, Atlanta, GA 30350

617-245-4958

8735 Dunwoody Place, STE R, Atlanta, GA 30350

617-245-4958

RSS Feed

RSS Feed