|

When it became clear that COVID-19 was coming to American shores, some of the first things to be cancelled were large entertainment events. A few weeks before tens of millions of Americans were unemployed across most sectors of the economy, some of the first few thousands suddenly without work were our nations’ performing artists. The early days of the crisis prompted my article about the short-term financial impact of COVID-19 on the finances of a performing artist. This article has been shared hundreds of times and has more than 15,000 page views – not a lot in the grand scheme of the internet, but staggering for a small non-profit arts organization like ours. Now, as the nation begins to contemplate how we might emerge from over a month of traumatic lockdowns, it is looking likely that the impact on live performing arts may be severe for a much longer time. Just as the concerts, plays, musicals, and operas were among the first things to be cancelled, these “non-essential” gatherings (they feel quite essential to the professionals who create them!), often reliant on large numbers of people, many in older age groups, will be among the last to return. We all hope for a vaccine to be developed in record time, or for a quick breakthrough in clinical treatments for COVID-19. But, the timing of these developments is unknown and completely out of our control. In a survey of our Skylark artists, the most common response for when concerts are likely to resume (economically, with an audience) was “sometime in the first half of 2021.” Many think that it could be later. How do we plan in such a time of jarring uncertainty? What happens if large audiences are afraid to return until we have successfully developed a vaccine? If the foundation of performing arts organizations is built on live performance, what are our options if large audiences are nearly impossible to assemble? If we assume that the strategy “hope for the best, wait and see, cancel, beg for money, rinse, repeat” is not a great plan, I think performing arts organizations have only two basic options:

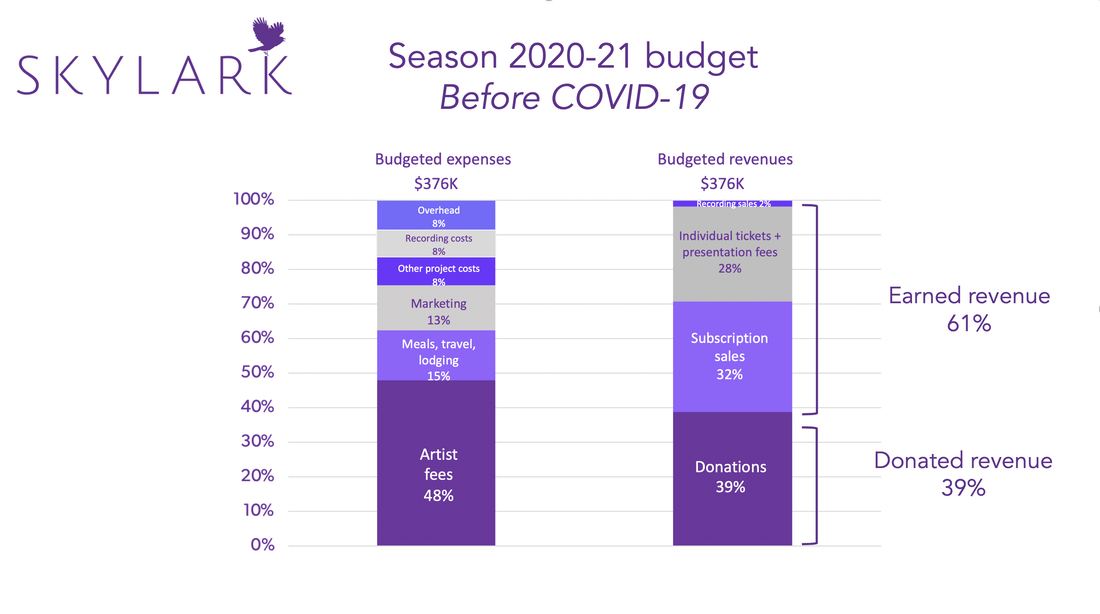

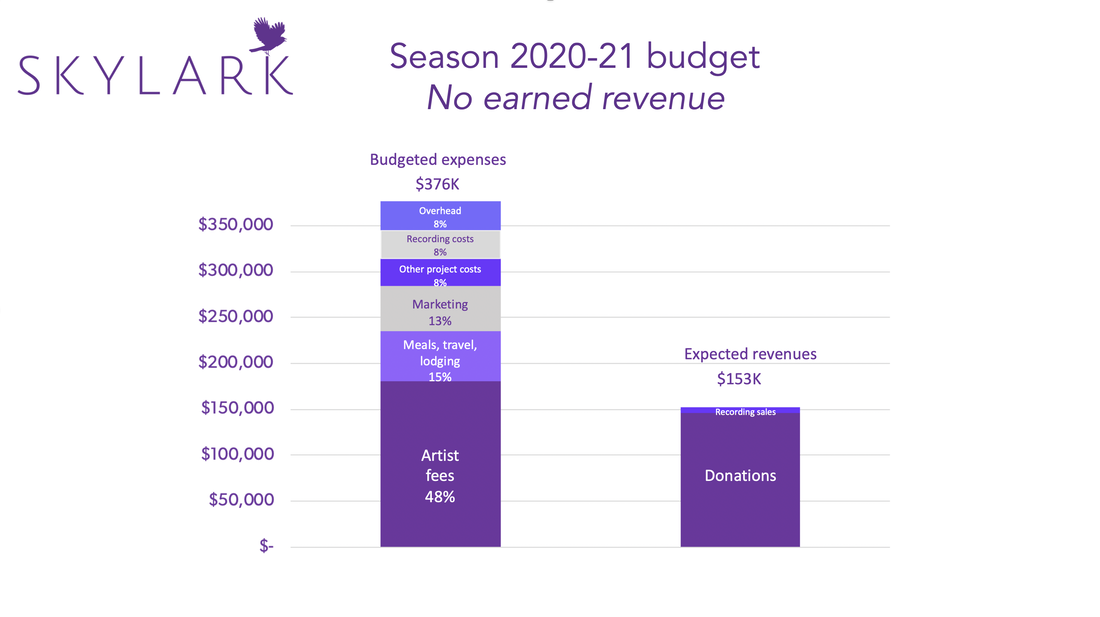

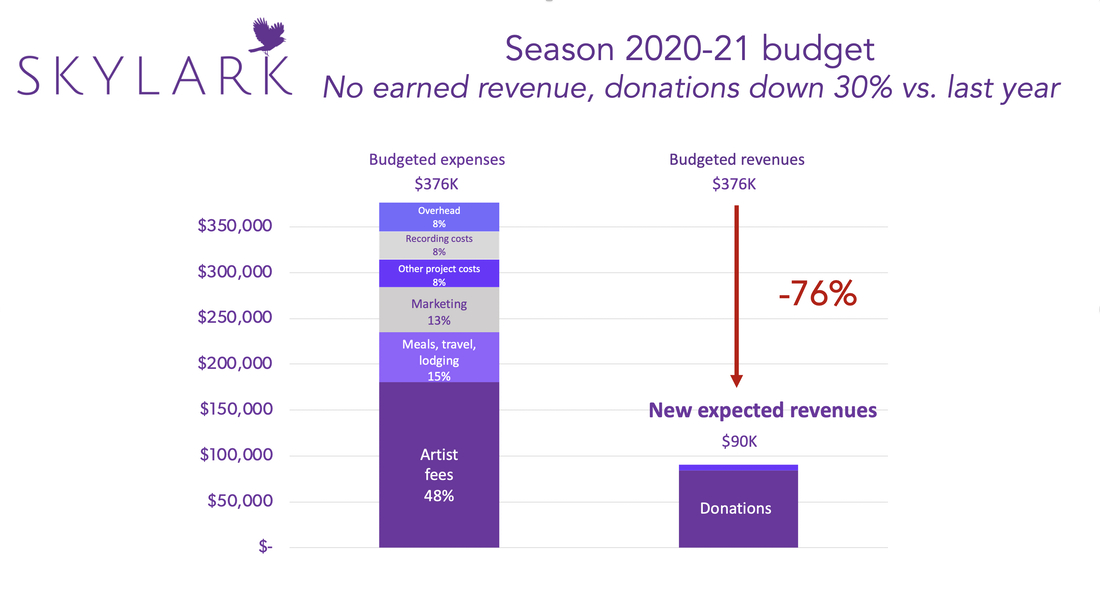

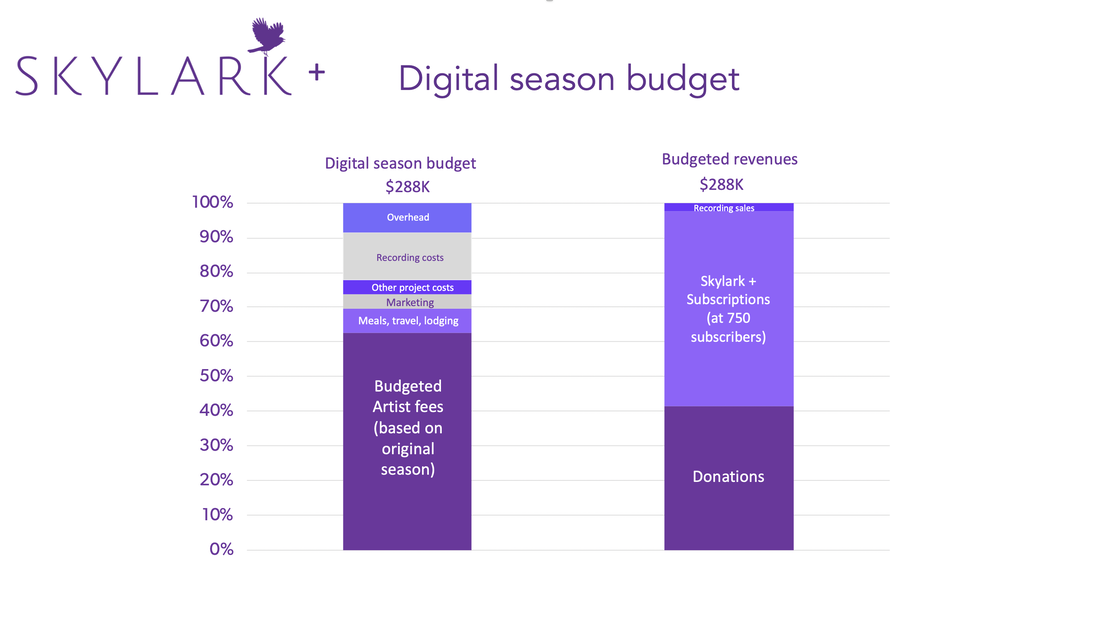

Neither of these options is easy. The first option is terribly sad for our audiences, and is fraught with acute pain for artists and staff in the form of furloughs and cancelled projects. The second path is exceedingly difficult and requires great flexibility and adaptation. At Skylark, we’re hoping to find a way to make the innovative path a reality. Our upended economic modelIt may be helpful to understand how Skylark’s economic model works. Skylark brings together world-class professional musicians to perform beautiful concerts on a project basis throughout our season. Our artists are at the top of their field, and Skylark is gaining increased recognition as one of the most exciting classical vocal ensembles in the United States (a recent album earned two GRAMMY® nominations). Next season, we have plans for eight projects bringing together a roster of over 20 musicians for a diverse series of concerts in the Greater Boston area. It is our most ambitious season yet, and has been in the planning for over eight months. Our artists were sent contracts back in December of 2019 for all of this work, and they have been relying on this income for next year. By far, the biggest portion of our budget (nearly 50%) is allocated to compensating our artists. The rest is made up of other project costs, marketing, recording, and some modest overhead expenses. Our revenue comes from two sources: Earned revenue: Money from season tickets, individual concert tickets, and presentation fees when we perform for large concert series Donated revenue: Tax-free donations from our subscribers and supporters Here is a snapshot of our budget before COVID-19: Our economic model is similar to many other organizations, with a few exceptions – first, we have a large percentage of earned revenue (in general, 50%+ is very good for a classical music organization), and we have very low overhead (we have a very small staff and no large fixed expenses like a building or theatre to maintain). What happens to this economic model if we are unable to present concerts for the entire season? First. our earned revenue will go to nearly $0. We might still manage a few thousand dollars of recording sales, but these will be paltry in the world of Spotify and Apple Music. Here’s that adjustment to our budget: Further, what happens to donated revenue in a time when concerts can’t take place? While we have no way of knowing for certain, I suspect it is not good. I know that many of our donors will continue supporting Skylark because they love our group and want our work to continue. However, with the stock market significantly down and unemployment through the roof, many of our supporters are facing financial troubles of their own. I would wager that a 30% reduction in donated revenue compared to our previous year would be a good scenario, and there are certainly worse scenarios that I can imagine. With those adjustments to a potential new reality, our total expected revenue drops a whopping 76%: On the upside, we will incur fewer costs! (?) Presumably travel costs would drop to zero, and we would have no need to spend money to market concerts that are not happening. However, we would still have a contractual and moral obligation to our singers. And while we certainly can invoke force majeure given the external forces at play, that doesn’t help our singers pay their bills or help us feel like good stewards of Skylark’s mission. What if we simply reduced our overhead as much as possible and turned Skylark into a charity that passed donations directly onto our singers? Our artists would see their Skylark income drop at least 60%. That is, if our donors did not get extremely fatigued being asked to support Skylark in a time when there are so many important charitable causes that need support. I’m not sure this would be true, and I suspect donations would drop even further. No one would feel good about this solution – not our artists, not our audiences, and not our donors. What else is there? Designing an interim model To think about a new solution, we had to think about what makes Skylark special to our subscribers and ticket buyers. We think it comes down to three things:

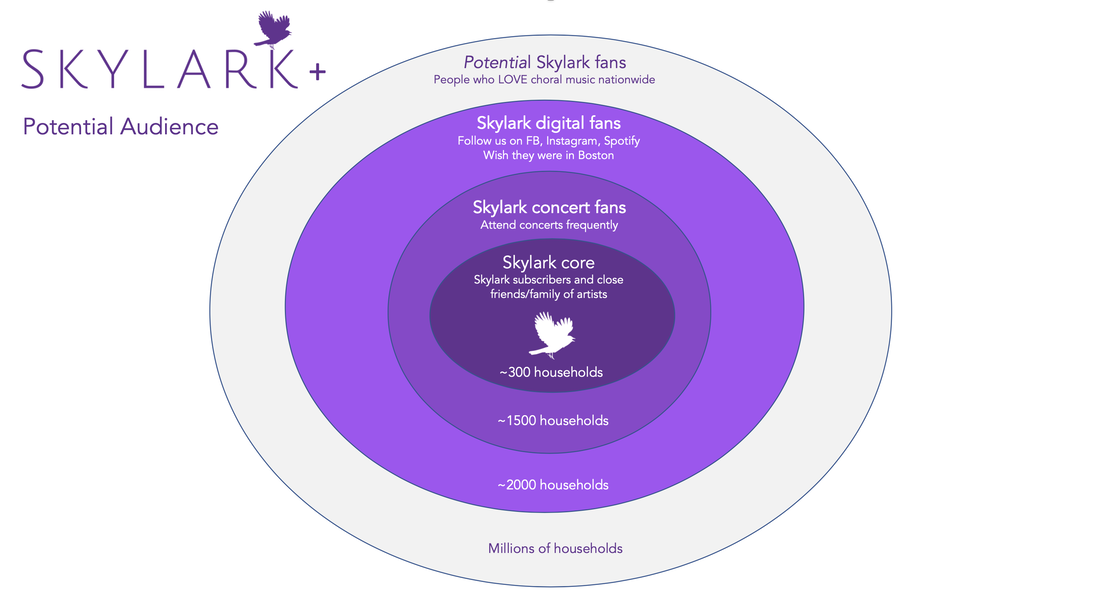

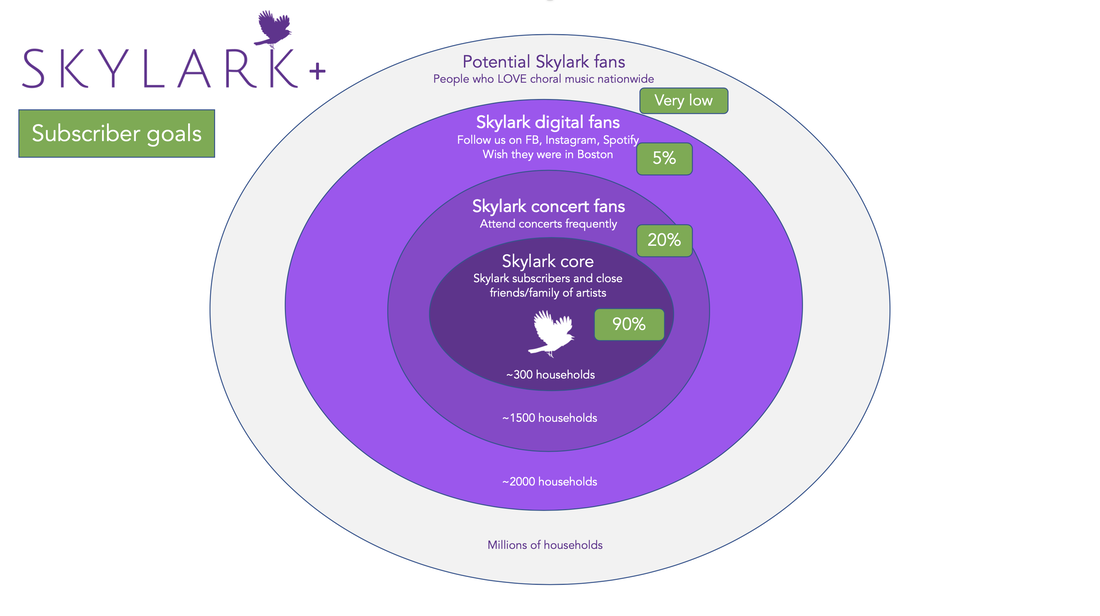

While it is certainly easier to do these things in a world built around live concerts, I don’t think it is impossible to do these things in the digital world, especially with the technology available today, and especially if we are engaging with the people who are already actively involved in the Skylark community. We thought about how to create a meaningful online community to serve these goals and came up with our concept for Skylark +. Here’s the video we created to launch the idea to our audience: After launching Skylark + this weekend, we have had an immediate positive response that has given us great optimism that this can and will work. I believe most of our fans and supporters will want to be a part of this new community and will understand it is the best we can do until we are together again in person. We aren’t experts at this yet. I’m sure navigating the technology in the early days will be frustrating. We will make mistakes. Over time, we will get better at creating videos and delivering digital content. We will develop even better ideas for engagement with our audiences. But, for the first time in six weeks, it feels like we have a way forward and a productive place to focus our artistic energy. The budget What could our budget look like in this new world? It is tempting to think that a digital model opens up the entire world to joining our online community. While this is technically true, the people who are likely to be first adopters are those who are already engaged supporters and attendees of Skylark. Last season, we had 330 subscribers in the Boston area. We had about 2,000 individual tickets buyers. We have an email list of ~2,300 people 3,000+ Facebook followers, ~1K Instagram followers, and about ~1K Spotify listeners in an average month. I think about the potential audiences as concentric circles around Skylark: Although anyone could join Skylark +, the likelihood is much higher in the closest circle of fans. I would wager we might convince 90% of these fans to subscribe (last year, our retention rate of subscribers was 99%!). Of the concert fans, I think we could aim for 1 in 5 attendees to join. Digital-only fans will be much less likely to pay for content, but perhaps 1 in 20 would subscribe. For the broader digital world, I think we might pick up a few subscribers, but it seems like a hard sell. Here’s what that looks like: If this were to be successful, we could realistically gain ~700-750 subscribers to Skylark + without having to recruit many subscribers from the broader community. If we retained these subscribers for a full season, we could even break even on a new digital season (with a lower budget for marketing, travel, and project costs) while reaching our original budget for artist compensation: It is still too early to know if these goals are realistic, but we are very excited to start down this road before a vaccine is developed. Even if live performance can’t happen for over a year, there could still be a way to take care of our artists, connect with our audiences, and create joy in the world.

As soon as we are able to plan concerts, we will be thrilled to do so. But, in the interim, we have an energizing new goal to pursue. And, we may even find that our digital community is something that people love and that we want to continue building for many years after COVID-19 is a blessedly distant memory.

2 Comments

Obviously, the biggest concern for all of us in our country right now is containing the spread of COVID-19 by #flatteningthecurve of the spread of the virus. Now is the time to take aggressive action to protect our healthcare system and save lives. If you are not yet fully informed on the importance of this effort, this excellent article provides compelling data. However, another huge concern is the economic impact on our world. For those of us in non-profits arts organizations, we are most concerned about the financial health of our individual artists. Skylark is made up of some of the finest ensemble musicians in the nation. Our artists are at the absolute top of their field. Many have multiple degrees in music. They are in demand on concert stages and in recording studios across the nation. They have been nominated for multiple GRAMMY Awards. What does COVID-19 mean for artists like this? In short, it is financially devastating. To understand this, let’s look at the career of a hypothetical highly successful freelance musician who earns her living on the concert stage. Let’s call her Emma. Here are a few things to understand about our hypothetical classical music rockstar:

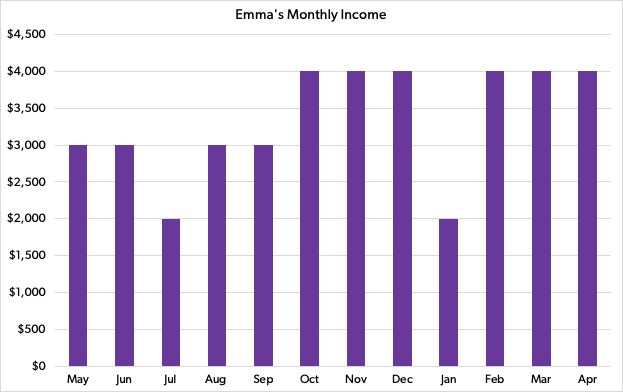

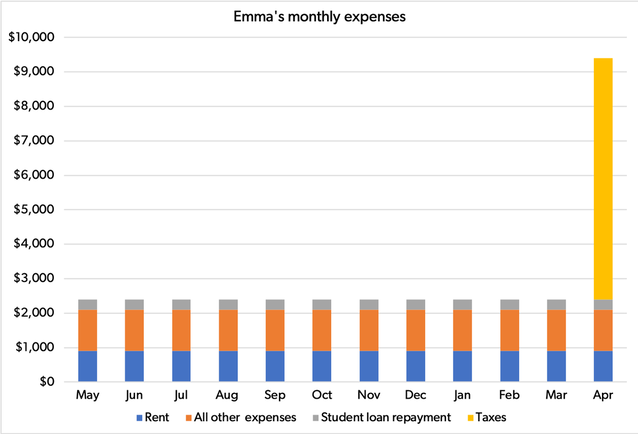

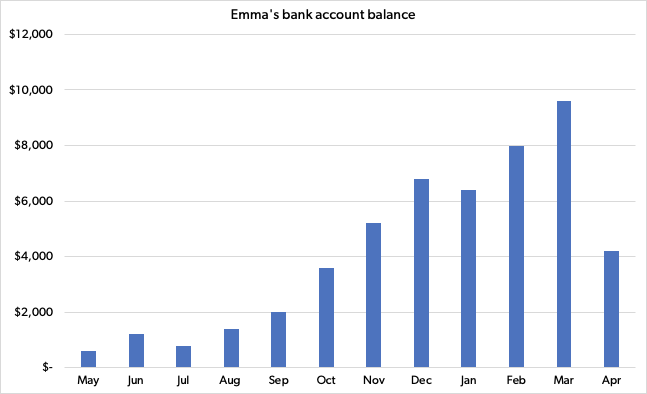

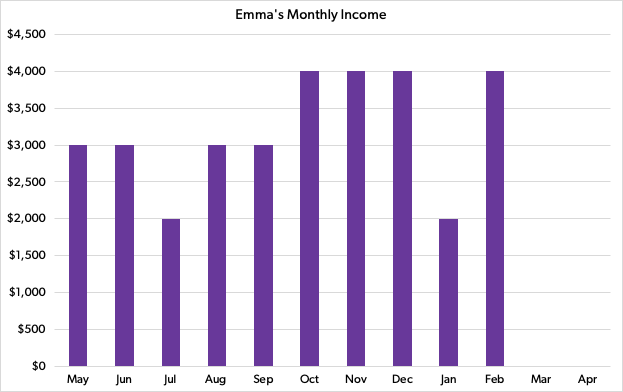

How does Emma do financially? Emma is one of the best in the country at what she does She keeps herself busy most of the year, and as able to make $40,000 over 12 months in her career as performer. This is very good. Her income in a typical year looks kind of like this, considering a 12-month period from May-April (April is last, because, well, taxes!) You probably noticed that Emma’s income is higher during the traditional music “Season” in the fall and Spring. There are fewer concerts in the summer and the ‘shoulder’ seasons, so her income is lower in those months. What do her expenses look like?

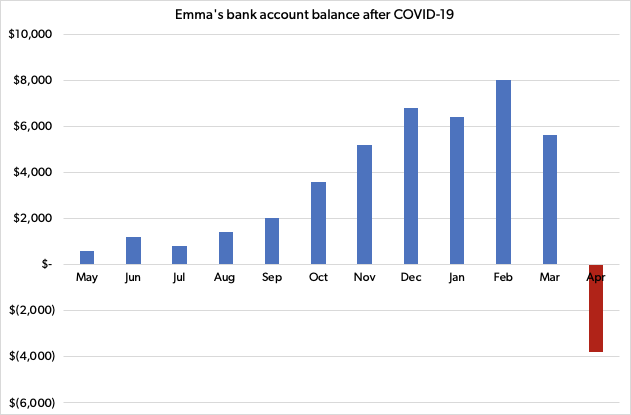

Here are Emma’s expenses by month: What does her financial plan look like for the year? Emma plans to SAVE 10% of her income this year, to start to build a nest-egg for her future. Here’s what she expects her bank account to look like at the end of each month based on her contracted work. Last week, Emma was very excited that she would meet her goal of saving over $4000 over 12 months. What does COVID-19 mean? This week, Emma has found out that all of her paid work for March and April has been cancelled, because each one of the arts organizations that hires her has been forced to cancel all public events. Even though the arts organizations have Emma’s best interest in mind, they unfortunately don’t have the money to pay her, because the ticket sales and concert fees will never materialize. What does Emma’s situation look like now? Here’s her income: Here are her expenses: Note, her tax bill hasn’t changed despite her lost income, because it only applied to January to December of the previous calendar year. How about her bank account balance? So, in the space of 5 days, a highly financially responsible professional has gone from a path of saving 10% of her income to having no way to support herself over the next few months.

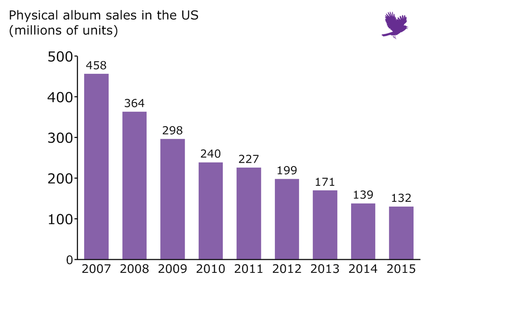

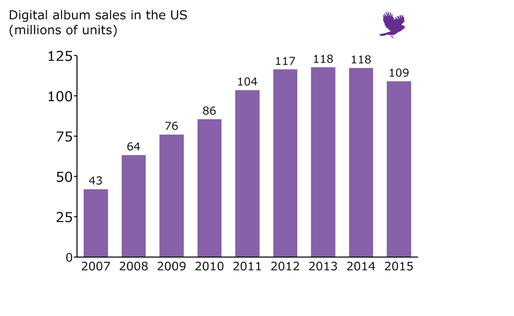

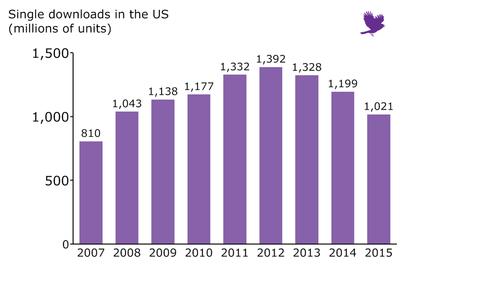

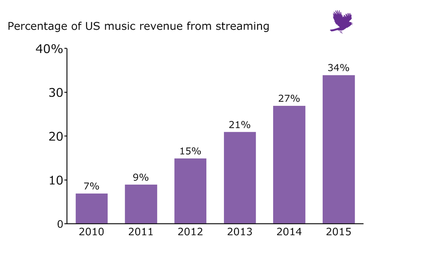

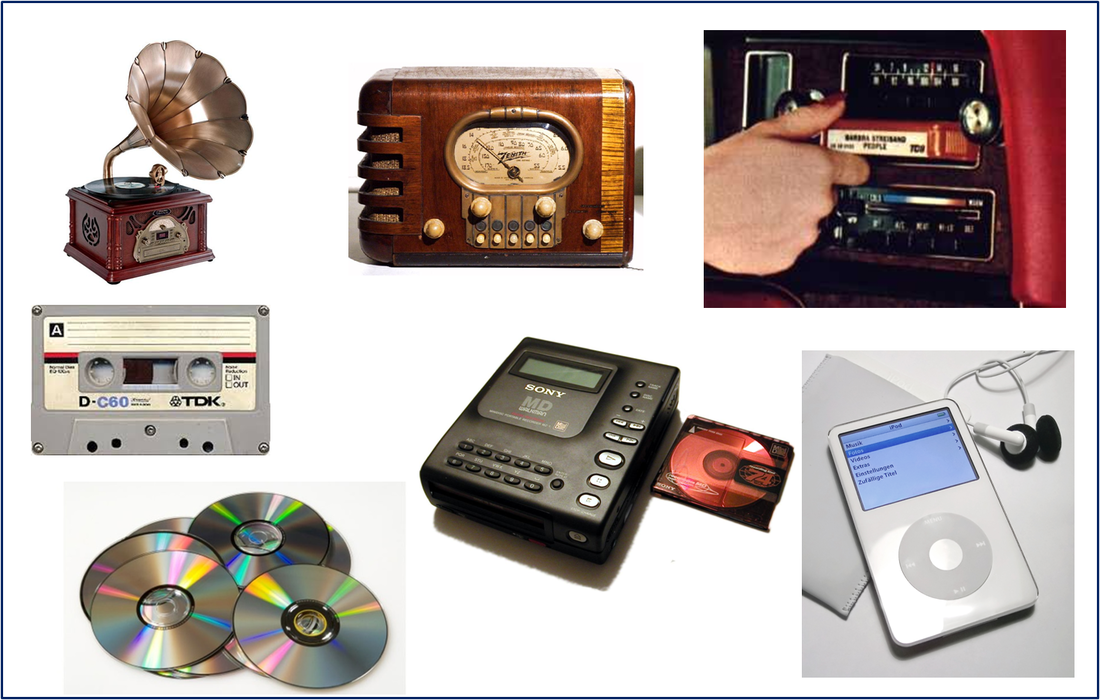

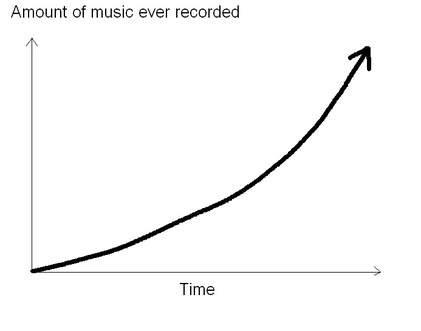

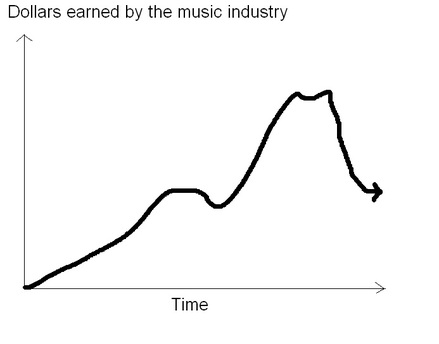

This is an absolutely terrifying situation. Of course, we hope for government action to help people like Emma (and countless other hourly workers or people in the gig economy, who have similarly scary situations). However, this support is not likely to come fast enough. What can we all do now? Think about performing arts organizations that are near and dear to you: choral ensembles, orchestras, string quartets, opera companies, theatre companies. Think about all of the people whose courage in pursuing a life in the arts makes great performances possible. Go to their website and donate today - it could make a huge difference in the life of artists like Emma. - Matthew Guard, Artistic Director, Skylark As you probably know, the digitization of music has reached a tipping point. And how amazingly convenient it is. I love being able to find almost any music I want in an instant, and play it through Spotify. I love using curated playlists from services like Pandora and Google Play Music. I am absolutely astounded by how these services allow us to find, organize, and play music of so many genres without having to navigate something like this: I feel so much cooler now that I don't have to walk around with one of these: And it is so awesome that I can play music uninterrupted for hours without investing in one of these behemoths: As a consumer of music, this new world ROCKS - what an amazing gift technology has brought us. This is a truly magical time! I feel like this puppy: But, as an Artistic Director of an independent classical music group, these magical times terrify me. I actually feel more like this: Why? Well, there are two big problems, and no easy solution. If you are a music lover, and especially if you love music of any kind from artists who do not top the international charts, I hope you will read this and consider your music purchasing behavior over the next few years. Problem 1: Awesome technology has seriously eroded dollars spent on musicThis is the obvious part of the story, but here’s a little data, just to make it real. Not surprisingly, physical CD sales are dwindling...to the tune of 8-10% a year over the last decade. This is pretty damn bad. Companies go bankrupt very quickly in markets with fundamentals like this. “Well,” you might say, “of course physical sales are down, but digital downloads of albums are up, right?” Actually, no, not anymore: "Wait, that's album sales, though....aren't single track downloads still rising? Nope: The most recent reports show digital downloads shrinking even faster than physical CD sales. Many music industry analysts believe that CDs will actually outlive downloads as a format. What is on the rise? Well, pretty much the only thing on the rise is streaming. On the upside, paid streaming is a LOT better than pirated streaming (like Napster). But, it is not nearly the lifevest that is needed for the recorded music industry to recover all of the value lost over the past decade. Even with massive growth in streaming, the global music industry (largely represented by the major labels and distributors, not the artists) grew less than 1% in 2015. It makes sense, right? Why on earth would you ever buy an album if you can stream it instantly from your phone for free (at best) or for an "all-you-can-eat" price of $10 a month for more music that you could ever listen to? For a whole generation that came of age in the last decade, the idea of buying music in physical album form is as foreign as a rotary telephone. Pretty soon, the digital download will be the same. The ash heap of antiquated music technologies will then look like this: What does this all mean? Well, to get really technical, In a world where the amount of music that has ever been recorded is growing, kind of like this: And when the amount of money is shrinking or stable, kind of like this: The dollars available for each piece of new recorded music looks kind of like this: Or alternatively, like this: It's not a great situation. To make matters worse, there's... Problem 2: Very few dollars spent on music ever make it to the artistsSince we were just talking about streaming, let’s start there. How economically different is streaming for an artist than selling an album? Let’s imagine for a moment that there are just two options in the world for listening to music:

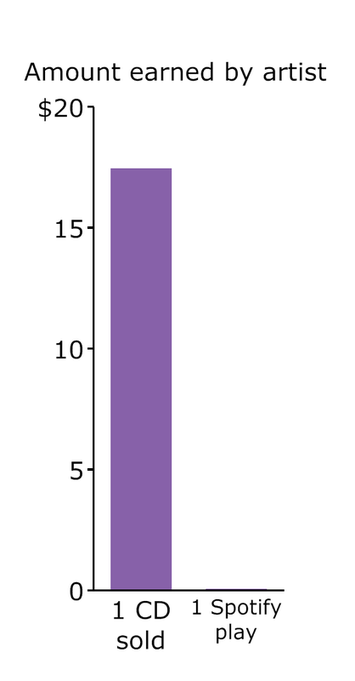

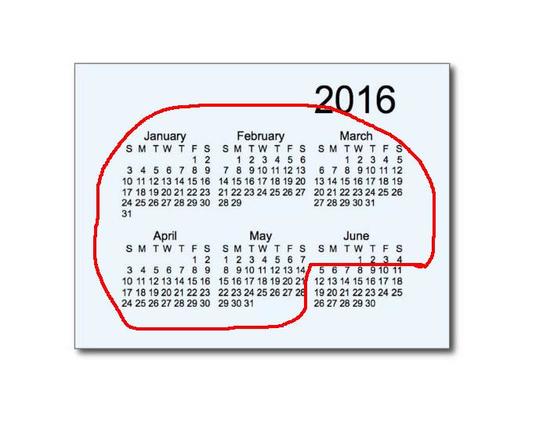

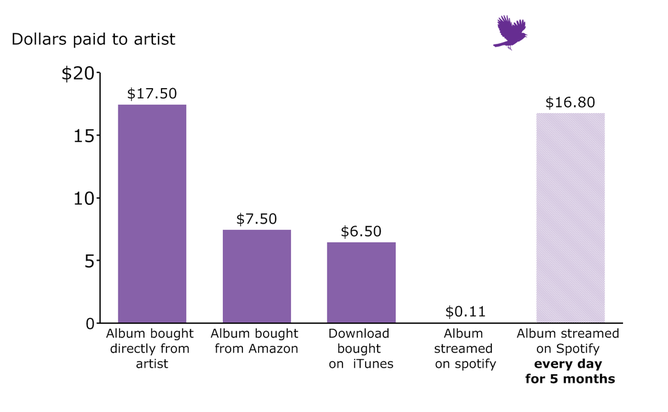

For Option A, let’s assume you pay the artist $20 for the disc, and we’ll estimate that the artist paid $2.50 to actually print the CDs and booklets. The artist nets $17.50. For Option B, let’s assume you listen to the entire album of 16 tracks on Spotify. The average track play on Spotify nets an artist .7 cents per play. Not 7 cents, 0.7 cents [$00.007]. For this full play of the album, the artist nets $0.11. Let’s just graph that up: Yikes! But wait, what if you played it a lot? Wouldn’t it get better? Well, of course, but it would take a LOT of plays. To be as well off as the $17.50 in Option A, it would take 2500 track plays. What does that mean exactly? If you listened to music for 14 hours a day every day, you would have to listen to NOTHING but that album for 12 days straight. Even if it is GREAT music, this would make almost anyone look like this: Or, perhaps more reasonably (?), let’s just imagine that you listen to the whole album just once per day. Because even if you love an album, once a day is enough, right? That would just mean listening to the album only on the days circled on this calendar: Ok, that's a lot of days! To think about it a different way, these two scenarios would be economically equivalent.

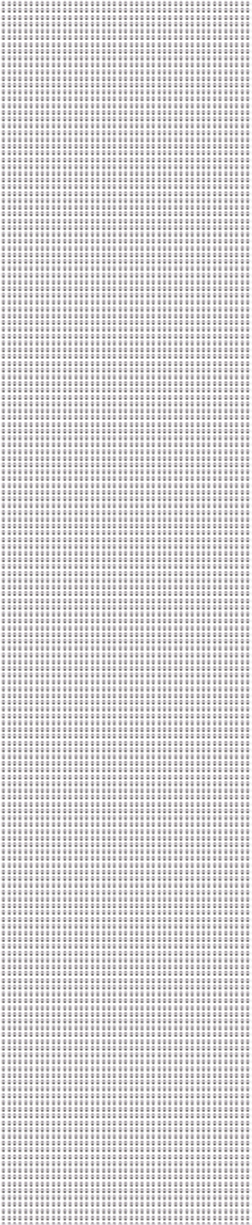

That's right! If you convinced ALL of these tiny smiling faces to listen to a track on Spotify: It would net the same amount of revenue as convincing all of these smiling faces to buy a physical album: This last makes me particularly queasy, as it means that the return on investment for any marketing in this age is bound to be remarkably low. You just need SO MANY people to listen. So, streaming (at least as it currently exists), is a bad substitute for album sales. Scary bad. Hopefully it will change in the future, but it won't happen overnight. Let’s add another option to our list above:

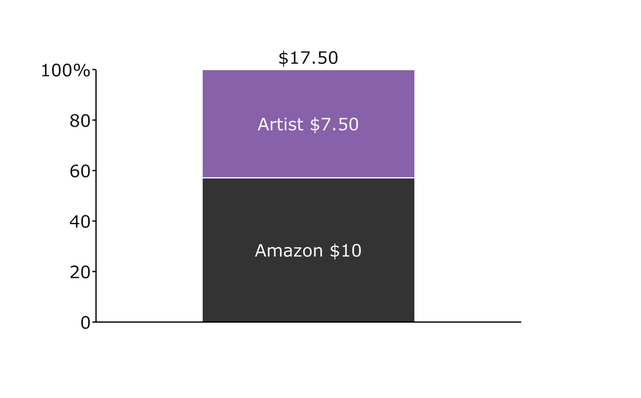

Amazon is now the top retailer of music in the US – they sold 24% of all CDs in 2014, and I’m guessing that number has gone up. Amazon reviews are incredibly important to album sales, and Amazon lists of top sellers help set the conversation of the market. Amazon is hard to ignore. Let’s imagine an artist decides to sell her album to Amazon at a wholesale price of $10. The album still cost her $2.50 to physically produce. In that situation, where does the money go? Yep, that’s right, Amazon nets the majority of the sale, and takes home more than the artist. I understand that Amazon provides an amazingly convenient service that consumers love, but boy, does that stat make me sad. Especially given articles like this. Now that we’ve been a little depressed by that, let’s add a fourth option to our list:

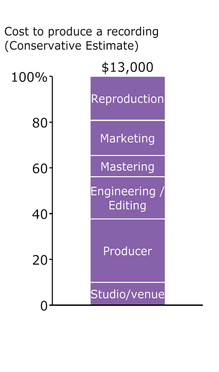

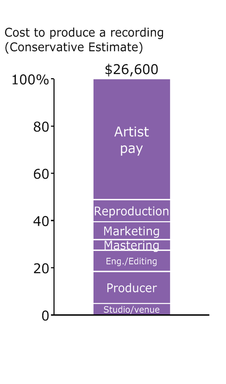

This is certainly better than streaming, and the artist doesn’t have to go through the cost of buying a CD. A $10 download on iTunes might result in the artist getting a check for $6.75 a few months after you downloaded the album. So, just to sum up the economics we just talked about, here’s what an artist nets in each of several scenarios: To this point, we haven’t considered ANY of the costs of creating a recorded album. These probably include:

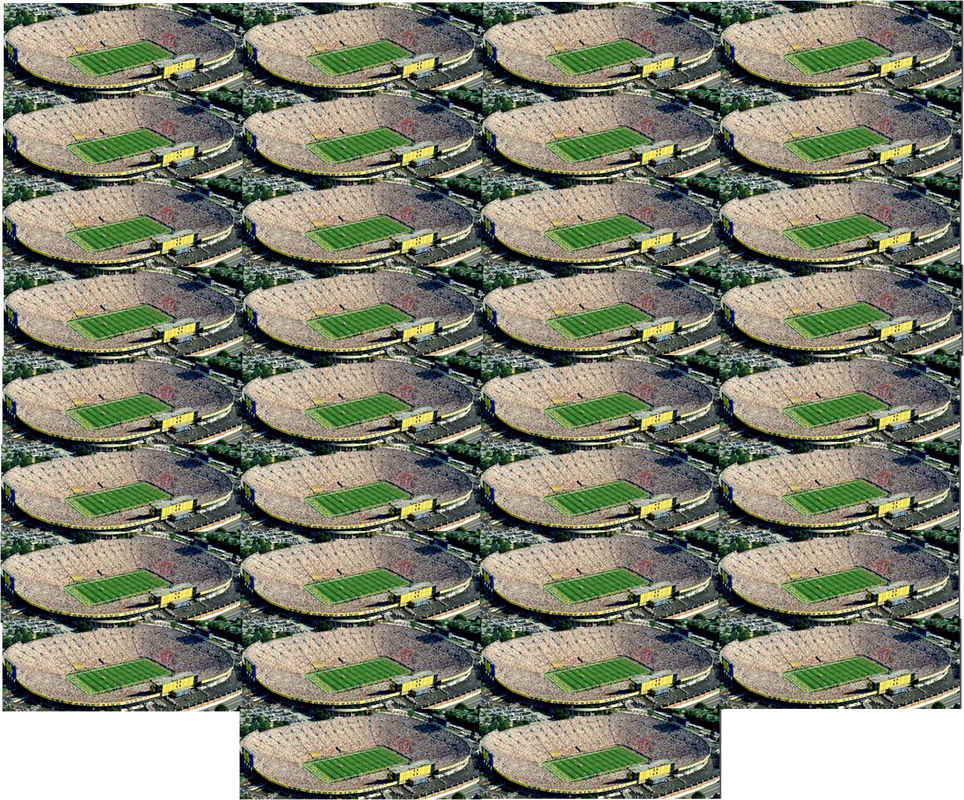

Let’s look at those in our conclusion… Conclusion: Creating new independent recordings (other than pop smash hits) may not be a viable business for much longerTo illustrate this, let’s imagine that a non-pop-mainstream musical group has a compelling new project they would like to record. They could be independent, classical, folk, whatever you like. If the artists themselves donated their time to the project (E.g., composed music, rehearsed it, and recorded it for free), the costs to put together the average album might look something like this: Ok, $13,000 doesn’t sound too bad, right? What would it take to make that back? [By "make it back" I mean cover costs - before generating any actual profit from the recording.] Well, it could take a variety of forms, but here’s one path to recovering just those costs in today's world: Hmm. Ok, what if we want the musicians to actually be compensated for their efforts? [Let's assume that the work is in the public domain - ignoring for now the possibility of a living composer, which would add to the cost as well.] Again, we’re estimating, but what if there were 16 professional musicians involved in the project, and they wanted to make a modest $25/hour for their time rehearsing and recording the project? [Aside: I believe that professionals should make much more than this, which is a whole different post altogether; I just choose this modest amount to illustrate the point. These could be people trying to make a living in the music industry, and have bills they need to pay.] The costs would then look like this: And the breakeven would be: That may not sound daunting, but, in the current music market, it truly is. To put this in perspective, if this were a classical album, it would likely need to be in the top 10 on the Billboard Classical chart for 6 straight weeks to reach this break even. That’s a tall order for anyone who is not Andrea Bocelli or Yo-Yo Ma. (Or the Star Wars sound track, the current #1 at the time of this post...). And that is based on the world today. What if we fast-forward to a world where streaming is the only form of revenue? At current stream rates, it would take 3.7 million track streams just to break even on this hypothetical project. Over 1% of all Americans would need to stream 1 track. That the equivalent of everyone in the state of Connecticut or the entire country of Panama. See this stadium? You would have to fill that stadium 34 times with different people who have sampled a track to break even on this relatively modest project. Can this possibly be viable in the future? It has never been easy for musicians to make money, but I fear the economics are turning even more sharply against artists. In a world with ever-growing (seemingly infinite?) content available, future economic rewards are likely to land disproportionately in the pockets of those companies who are able to use technology to harness and curate the vast amount of art available. That is a valuable thing, of course. But what about the art itself? What about the artists? What happens to new art creation in a world where people are conditioned to believe that music is free? Some artists will be more likely to succeed in this new world - particularly those who are clever and adaptable to technological and societal trends around digital content consumption. But many others will not. Great artists are not necessarily great digital marketers or technical gurus. Some great art will not happen. Important recordings will never take place, because it will not make economic sense. A reasonable person might say: "Yes, Matthew, but isn’t this just an issue of simple supply and demand? It seems that there is just too much recorded music already available, and the willingness to pay is low simply because there is so much of it. We have enough albums already, we don’t need to make any more unless they are going to be heard by millions of people." If you believe that the popularity of music is the only measure of its value, and you think that only artists who make the top 40 are worthy of documenting their work and reaching people through their recordings, this is exactly right. You can close this page now. But, I don’t believe that. I believe that it is vital that performing musicians feel inspired and financially able to record music that will not be #1 on the pop charts. I believe that a rich society needs living performers of music of many genres. I believe that audiences of independent artists want to have recordings of their favorite musicians so that they can be moved by music outside of live performances. I believe that there are relevant and new artists and compositions that need to be added to the existing canon. I believe that artists need recordings of their work to help reach audiences they never see in person. Most of all, I believe we need active artists in our world, as art has the power to bring human beings together in a time when our politics, our culture, and our global economy often have a tendency to divide us. I think things need to change. But how?

|

| Heyr þú oss himnum á, Guð. Heyr þú oss himnum á, hýr vor faðir, börn þín smá, lukku oss þar til ljá líf eilíft þér erfum hjá, og að þé r aldrei flæmumst frá. Þitt ríki þró ist hér, það þín stjó rn og kristni er, svo að vé r sem flestir, Guð, til handa þér, fegin yfir því fögnum vér. Síst skarta sönglist má, sé þar ekki elskan hjá, syngjum þvíþýtt lof þá, Þér, Guð drottinn, himnum á, Maður rétt kristinn mun þess gá . En þegar aumir vér, öndumst burt úr heimi hér, oss tak þá , Guð, að þér, Í þá dýrð, sem aldrei þver. Amen, amen það eflaust sker. | Hear us in heaven, O God. Hear us in heaven, loving Father, as we, your small children, ask for the fortune to receive eternal life. We shall not stray from your path. May we help your kingdom to grow here on earth. Following your guidance, we gather around in your name, and gladly celebrate. We cannot make a joyful song unless we are moved by love. So let us sing our gentle praise to you, Lord God, in heaven, as the truly faithful have done. When our poor souls pass away from this world, take us God to you, into your everlasting glory. Amen, Amen, may this be done. —Old Icelandic Psalm |

We who remain

Funeral Ikos, John Tavener

At this point on the disc, our protagonist has crossed over to what may lie beyond.

We are left here, on earth, wondering what has happened.

Our program returns to John Tavener, and his Funeral Ikos (with a text from the Greek Orthodox Order for the Burial of Dead Priests) ponders the mystery of where our loved ones have gone and where we may someday go ourselves.

The piece is a simple chant, and over-analysis defeats the purpose. We strove to deliver the text in as compelling and honest a way as we could.

The only thing I will offer is that Tavener’s indicated tempo is far faster than any professional recording I have heard before ours. At this faster tempo (still slightly below the 88 beats per minute in the score), I think the piece takes on an urgency and an emotional life that is missing in slower versions.

The piece and the album end on a stark open fifth. We have progressed through a series of dreams and visions, and witnessed someone cross over into the beyond, but we as humans on earth still lack a clear image of what is to come.

We are left here, on earth, wondering what has happened.

Our program returns to John Tavener, and his Funeral Ikos (with a text from the Greek Orthodox Order for the Burial of Dead Priests) ponders the mystery of where our loved ones have gone and where we may someday go ourselves.

The piece is a simple chant, and over-analysis defeats the purpose. We strove to deliver the text in as compelling and honest a way as we could.

The only thing I will offer is that Tavener’s indicated tempo is far faster than any professional recording I have heard before ours. At this faster tempo (still slightly below the 88 beats per minute in the score), I think the piece takes on an urgency and an emotional life that is missing in slower versions.

The piece and the album end on a stark open fifth. We have progressed through a series of dreams and visions, and witnessed someone cross over into the beyond, but we as humans on earth still lack a clear image of what is to come.

Welcome to part 2 of the story of Crossing Over, where we continue the narrative of our album. To read part 1, click here.

A painful memory

Requiem, Jón Leifs

After a moment of stillness and clarity in the Kedrov Our Father, we shift to a new harmonic center for Leif’s stunning Requiem, dropping a minor third to A. We retain the homophonic texture of the Kedrov, but it becomes shrouded by an aching feeling of grief.

For someone nearing death, I feel this is one of those blurred dreamlike images of things long past – of dear ones loved and lost. A duality between joy and sadness: grieving for loved ones whose lives have ended, but grateful for a life filled with love.

Leifs is best-known for his orchestral music, which is quite tempestuous (described as “brutal” and “primordial”), and oft based on natural phenomena of his extremely geologically volatile native country of Iceland (think volcanoes and waterfalls).

His Requiem is quite different in feel than the rest of his output, likely because it emerged from a time of profound personal tragedy.

In 1947, his daughter Lif drowned while swimming off the coast of Sweden shortly before her 18th birthday. In the weeks that followed, Leifs composed his Requiem while his family was bringing her body to Iceland for burial.

Our image from the album notes attempts to capture the profoundly somber feeling of the piece.

For someone nearing death, I feel this is one of those blurred dreamlike images of things long past – of dear ones loved and lost. A duality between joy and sadness: grieving for loved ones whose lives have ended, but grateful for a life filled with love.

Leifs is best-known for his orchestral music, which is quite tempestuous (described as “brutal” and “primordial”), and oft based on natural phenomena of his extremely geologically volatile native country of Iceland (think volcanoes and waterfalls).

His Requiem is quite different in feel than the rest of his output, likely because it emerged from a time of profound personal tragedy.

In 1947, his daughter Lif drowned while swimming off the coast of Sweden shortly before her 18th birthday. In the weeks that followed, Leifs composed his Requiem while his family was bringing her body to Iceland for burial.

Our image from the album notes attempts to capture the profoundly somber feeling of the piece.

Only five minutes in length, he sets a collage of Icelandic folk images and poetry.

The text is quite spare, focusing on simple images of death in nature, interspersed with highly personal poetic excerpts that bring Leif’s own tragedy into focus.

The music reflects this simple elegance. The feel is of a gentle but moving funeral procession in the Icelandic folk tradition (andante, molto tranquillo). The strong downbeat of each bar also creates an almost wave-like motion to the music, which is particularly compelling given the story of the piece.

Almost the entire piece is some variation of an A chord – major, minor, and an open fifth. The harmonic shifts through these variations are sudden and frequent, like the pangs of remorse and happy memories that come during a time of tragedy - it is as if every few measures takes us through several stages of grief.

As you listen to the recording, glance at the text and translation provided below. One of our own basses, Peter Walker, spent a lot of time crafting and editing an existing version of the English translation because he was passionate about retaining the metrical feel and powerful alliteration of the original Icelandic lullaby form. Peter read this in our concerts before we sang the piece, and I think it took the experience to an entirely new level for all of us.

| Sofinn er fifill fagr í haga, mús undir mosa, már á báru, lauf á limi, ljós í lofti, hjörtr á Heiði en í hafi fiskar. Sefr sell í sjó, svanr á báru, már í holmi, maangi au svæfir. Sofa manna börn í mjúku rúmi, bía og kveða, en babbi þau svæfir. Sof þú nú sæl og sigrgefin. Sofðu eg unni þér. Sofinn er fifill fagr í haga, mús undir mosa, már á báru, Blæju yfir bæ búanda lúins dimmra, drauma dró nóttúr sjó. Við skulum gleyma grát og sorg; gott er heim að snúa. Láttu þig dreyma bjarta borg, búna þeim, er trúa. Sofinn er fifill fagr í haga, mús undir mosa, már á báru, Sof þú nú sæl og sigrgefin. Sofðu, eg unni þér. From Icelandic folk poetry and Magnusarkvioa by Jonas Hallgrimsson | The fair flower sleeps in the field, The mouse under moss, The mew gull on the swell, The leaf on the limb, The light in the lofty air, The hart on the heath, And the haddock in the ocean. The seal sleeps in the sea, The swan on the wave, The mew gull on the rock-isle, With no one to lull them. The young child sleeps In a soft bed, Cooing and prattling, As a parent lulls her. Sleep now saintly and sanctified. Sleep, I love you. The fair dandelion sleeps in the field, The mouse under moss, The mew gull on the swell, A veil covers the village The man is very tired Dreams drew dark night from the sea. We should say goodbye To grief and sorrow, And go home to happiness. May you dream of the shining city, Where the souls of the faithful dwell. The fair dandelion sleeps in the field, The mouse under moss, The mew gull on the swell, Sleep now saintly and sanctified. Sleep, I love you. Poetic English translation edited and modified by Peter Walker (source of original translation unknown) |

Denial

Heliocentric Meditation, Robert Vuichard

Excerpts from Meditation XVII

PERCHANCE he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill that he knows not it tolls for him...

…Who casts not up his eye to the sun when it rises?...No man is an island…every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main…All mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language…God’s hand is in every translation, and His hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again, for in that library every book shall lie open to one another…Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

—John Donne

PERCHANCE he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill that he knows not it tolls for him...

…Who casts not up his eye to the sun when it rises?...No man is an island…every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main…All mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language…God’s hand is in every translation, and His hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again, for in that library every book shall lie open to one another…Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

—John Donne

After the achingly sad but somewhat disembodied Reqiuem, our next piece takes us to a more outwardly expressive place, in a world premiere recording of Heliocentric Meditation by composer Robert Vuichard.

I feel this piece as the apex of the album.

For the person approaching death, this is the moment of crisis, of tortured uncertainty over whether he or she is part of something larger, or simply an island that will sink back into the sea.

It is also an extremely hallucinatory moment. It has passages that feel like they could emerge from the medication-induced haze that many 21st century people experience in their final hours in a hospital.

I’ve talked to Robert at length about this piece. He is trying to capture the eternal struggle “are we a part of something larger”…“if one man dies, does the whole world mourn?”

He does so by alternating between human questions (expressed through small group or homophonic sections) and universal (as in the broader universe) images created through vast spatial cascades that break the choir into 12 parts. "From earthly space to heavenly space and back again."

It is the longest piece on the album, and it goes through striking evolutions as the piece alternates between textures and textual ideas. Some dissonances are deeply unsettling, while some of the cadences are truly ecstatic.

As I listen, I find my imagination alternating between images of my world (faces of loved ones) and visions of the absurdly larger universe (huge stars or planets radiating energy photographed by the Hubble telescope) that make my individual perspective seem trivial.

I feel this piece as the apex of the album.

For the person approaching death, this is the moment of crisis, of tortured uncertainty over whether he or she is part of something larger, or simply an island that will sink back into the sea.

It is also an extremely hallucinatory moment. It has passages that feel like they could emerge from the medication-induced haze that many 21st century people experience in their final hours in a hospital.

I’ve talked to Robert at length about this piece. He is trying to capture the eternal struggle “are we a part of something larger”…“if one man dies, does the whole world mourn?”

He does so by alternating between human questions (expressed through small group or homophonic sections) and universal (as in the broader universe) images created through vast spatial cascades that break the choir into 12 parts. "From earthly space to heavenly space and back again."

It is the longest piece on the album, and it goes through striking evolutions as the piece alternates between textures and textual ideas. Some dissonances are deeply unsettling, while some of the cadences are truly ecstatic.

As I listen, I find my imagination alternating between images of my world (faces of loved ones) and visions of the absurdly larger universe (huge stars or planets radiating energy photographed by the Hubble telescope) that make my individual perspective seem trivial.

It has been three months since we released Crossing Over.

In the time since the release, I have been deeply moved by personal stories of people who have been touched by our album. Some stories have come from a time of acute personal grief. For others, hearing the music has brought back memories of an intense past experience. These stories have furthered my belief that music has the ability to communicate truths in a visceral way that speaks directly to the heart.

As a thank you to those people who have shared their personal stories, I want to share more about what the album means to me. Over the course of several posts, I will share the progression of Crossing Over, with texts, images, musical impressions, and musical clips.

This first post will take us through the first 10 tracks of Crossing Over, including pieces by Daniel Elder, John Tavener, and Nicolai Kedrov.

My hope is that through sharing more about how the album came to be and what the music means to me and to us, the story it tells will reach and move even more people.

In the time since the release, I have been deeply moved by personal stories of people who have been touched by our album. Some stories have come from a time of acute personal grief. For others, hearing the music has brought back memories of an intense past experience. These stories have furthered my belief that music has the ability to communicate truths in a visceral way that speaks directly to the heart.

As a thank you to those people who have shared their personal stories, I want to share more about what the album means to me. Over the course of several posts, I will share the progression of Crossing Over, with texts, images, musical impressions, and musical clips.

This first post will take us through the first 10 tracks of Crossing Over, including pieces by Daniel Elder, John Tavener, and Nicolai Kedrov.

My hope is that through sharing more about how the album came to be and what the music means to me and to us, the story it tells will reach and move even more people.

Why this? Why now?

People who have had near-death experiences have described vivid images of what they saw and felt as they approached what could have been the end of life. We may go through a similar experience as we prepare to leave this world for what, if anything, lies beyond.

The pieces we have assembled on this album are musical meditations and visions on what that experience of 'crossing over' could be for each of us.

Crossing Over is not meant to be morbid or terrifying – in fact, some of the pieces are profoundly calm and beautiful.

The overall experience of the album is a varied journey that attempts to capture the extremes of emotion that we might feel in a suspended dream state near the end of this part of our journey.

In the inside cover of the album is the first of many gorgeous original polaroid photos by Caleb Nei and Collin Rae of Sono Luminus.

The pieces we have assembled on this album are musical meditations and visions on what that experience of 'crossing over' could be for each of us.

Crossing Over is not meant to be morbid or terrifying – in fact, some of the pieces are profoundly calm and beautiful.

The overall experience of the album is a varied journey that attempts to capture the extremes of emotion that we might feel in a suspended dream state near the end of this part of our journey.

In the inside cover of the album is the first of many gorgeous original polaroid photos by Caleb Nei and Collin Rae of Sono Luminus.

A low horizon with a focus on the sky, a bit of blur, a hint of light and hope.

On that page, we introduce our concept:

On that page, we introduce our concept:

What awaits us at the end? What will our final hours feel like? What memories will flit through our consciousness? What dreams? What visions? What emotions will we feel? Whose is the last face we will see? What, if anything, will lie beyond?

Crossing Over is a window into our collective imagination, a musical narrative of what our final hours may feel like.

Perhaps through imagining our last hours on earth, we can better prepare ourselves to face our time when it comes. Perhaps through imagining a fate we all share, we can better understand each other and our common bonds. Perhaps through imagining how we might feel when looking back on our life, we can focus more clearly on what we wish to do with each day that we have.

Crossing Over is a window into our collective imagination, a musical narrative of what our final hours may feel like.

Perhaps through imagining our last hours on earth, we can better prepare ourselves to face our time when it comes. Perhaps through imagining a fate we all share, we can better understand each other and our common bonds. Perhaps through imagining how we might feel when looking back on our life, we can focus more clearly on what we wish to do with each day that we have.

Near the end, a vision

Elegy, Daniel Elder

Our journey begins with Elegy, by American composer Daniel Elder. For us, this piece represents the moment of realization that we may be reaching the end of our mortal life.

Our image from the album notes captures a sense of frailty that this piece conveys, but also with an appreciation of beauty in the world:

Our image from the album notes captures a sense of frailty that this piece conveys, but also with an appreciation of beauty in the world:

Daniel and I talked at length about his vision for the spatial effects in his piece.

Perhaps we are walking into a valley where there is a small group gathered around for a memorial. The terracing of dynamics at the beginning and the end helps create a feeling of motion in and out of a scene.

Throughout, the altos also create the feeling of a broader space through lingering on after many of the chords cut off. They always linger on the tonic of the chord - perhaps representing the memory of each of us that remains when we are gone?

A gorgeous soprano canon in the middle of the piece hovers above an ethereal texture from the choir, creating the feeling of a transcendent bugle call (from above?) that echoes through time and space. The first soprano voice (Sarah Moyer) is clear and present, while the echoes (Margot Rood and Jessica Petrus) are further away, slightly veiled by distance.

After bursting out of introverted reflection into a moment of thanks, the piece retreats into a final section which Daniel describes as a raw and emotional lament. Odd staccato figures and voice leaps animate sudden pangs of tears, or brief sobs cut short by lack of breath.

Listen to our recording that Daniel shared on YouTube, which also allows you to follow along with the music:

Perhaps we are walking into a valley where there is a small group gathered around for a memorial. The terracing of dynamics at the beginning and the end helps create a feeling of motion in and out of a scene.

Throughout, the altos also create the feeling of a broader space through lingering on after many of the chords cut off. They always linger on the tonic of the chord - perhaps representing the memory of each of us that remains when we are gone?

A gorgeous soprano canon in the middle of the piece hovers above an ethereal texture from the choir, creating the feeling of a transcendent bugle call (from above?) that echoes through time and space. The first soprano voice (Sarah Moyer) is clear and present, while the echoes (Margot Rood and Jessica Petrus) are further away, slightly veiled by distance.

After bursting out of introverted reflection into a moment of thanks, the piece retreats into a final section which Daniel describes as a raw and emotional lament. Odd staccato figures and voice leaps animate sudden pangs of tears, or brief sobs cut short by lack of breath.

Listen to our recording that Daniel shared on YouTube, which also allows you to follow along with the music:

In and out of consciousness

Butterfly Dreams, John Tavener

After the prologue of Elegy, John Tavener’s Butterfly Dreams places the choir and listener into a dream state.

I feel the entire piece as a suspended period of pseudo-consciousness – a bit like dreams that you have in the morning when you are beginning to wake up, where you are somewhat aware that you are dreaming, but are able to suspend disbelief and commit to the visions that continue to flit through your mind.

I imagine that many people who reach the end of life may also experience this type of sensation in the final days or hours, in moments where visions of their life past and possibilities of an unknown future float through their mind.

Our image brings to mind these blurred images - without specificity, but full of warmth and color:

I feel the entire piece as a suspended period of pseudo-consciousness – a bit like dreams that you have in the morning when you are beginning to wake up, where you are somewhat aware that you are dreaming, but are able to suspend disbelief and commit to the visions that continue to flit through your mind.

I imagine that many people who reach the end of life may also experience this type of sensation in the final days or hours, in moments where visions of their life past and possibilities of an unknown future float through their mind.

Our image brings to mind these blurred images - without specificity, but full of warmth and color:

In his own notes, Tavener offered insight into his vision for the piece:

I regard Butterfly Dreams as a sacred work. Native Americans celebrated the pure metaphysics of virgin nature, and insofar as virgin nature is a manifestation of the Logos (the Word of God), Butterfly Dreams is intrinsically a sacred work. The texts are taken from different sources, including Chuang Tse, an Acoman Indian, and a poem written by a young Czech victim of Auschwitz. All the poems share an almost child-like simplicity, and I have tried to reflect this in the music, which should be sung as simply and as naturally as possible.

1. Butterfly Dreams based on Chuang Tse

Tavener’s inspirational text for the piece, and text for the first movement, comes from the 4th Century B.C. philosopher Chuang Tse:

“Which am I really? A butterfly dreaming that I am a man, or a man dreaming that I was a butterfly? The answer is neither of these: there were two unreal modifications of the Single Being, of the universal norm, in which all beings in their state are one.”

“Which am I really? A butterfly dreaming that I am a man, or a man dreaming that I was a butterfly? The answer is neither of these: there were two unreal modifications of the Single Being, of the universal norm, in which all beings in their state are one.”

Tavener’s setting of this existential uncertainty is brilliant in its simple reinforcement of the text. Five voices sing a quite simple figure in the key of G major, and the other five voices sing the same exact figure as a “shadow” canon two beats later.

The message is clear: whether man or butterfly, we are part of the same overall story, though the uncertainty of what we are does create confusion and perhaps even richness in life (demonstrated here by lush chords of choirs whose vertical harmonics do not always line up).

The overall piece is remarkably slow (quarter note = 40) and marked as “magical and exquisite” which perhaps indicates a true respect and fascination for the central concept…or perhaps just indicates that the person experiencing the emotions of the piece is in a state of REM sleep when his or her heartbeat has slowed considerably.

The message is clear: whether man or butterfly, we are part of the same overall story, though the uncertainty of what we are does create confusion and perhaps even richness in life (demonstrated here by lush chords of choirs whose vertical harmonics do not always line up).

The overall piece is remarkably slow (quarter note = 40) and marked as “magical and exquisite” which perhaps indicates a true respect and fascination for the central concept…or perhaps just indicates that the person experiencing the emotions of the piece is in a state of REM sleep when his or her heartbeat has slowed considerably.

2. Haiku by Kokku

Over the Dianthus, See.

A white butterfly,

whose soul I wonder.

A white butterfly,

whose soul I wonder.

Tavener’s second movement is a touch more literal and concrete. It begins at 60 beats a minute, and up a dynamic level. Perhaps slightly more awake and resting than the first movement. However, it still retains the shadowing effect, indicating that the dream is still present.

In my score I have written “in the air”…I see a very clear image of a beautiful white butterfly hovering over a flower (the Dianthus). I think the emotional feeling is: “The butterfly is so beautiful…I wonder what it means? Does it have a soul? Do I have soul? Are we one in the same?”

In my score I have written “in the air”…I see a very clear image of a beautiful white butterfly hovering over a flower (the Dianthus). I think the emotional feeling is: “The butterfly is so beautiful…I wonder what it means? Does it have a soul? Do I have soul? Are we one in the same?”

3. Haiku by Buson

Butterfly in my hand,

as if it were a spirit,

unearthly, insubstantial

as if it were a spirit,

unearthly, insubstantial

If movement 2 was watching a real butterfly “in the air,” this movement turns a bit more hallucinatory: the butterfly is now sitting “in my hand.” Tavener’s marking “unearthly” reinforces that a moment such as this likely could not be real, but only possible in a dream.

Much of the choir slows to a single C major chord, representing a moment of stillness (the butterfly has momentarily landed), while two parts (the soprano and alto), sing a gorgeously simple duet. This two-part harmony still illustrates the duality and oneness of human and butterfly soul – in this instance calmly and beautifully co-existing

Much of the choir slows to a single C major chord, representing a moment of stillness (the butterfly has momentarily landed), while two parts (the soprano and alto), sing a gorgeously simple duet. This two-part harmony still illustrates the duality and oneness of human and butterfly soul – in this instance calmly and beautifully co-existing

4. Haiku by Issa

The flying butterfly, I feel myself a creature of dust.

After moments of calm, chaotic energy emerges: a cascading 12-part canon paints a sonic picture of a dozen independent butterflies flitting around a garden.

Through 4 repeats, the canon cycles through several modal variations before returning to the original C major figure, perhaps signifying that there are only slight variations in each life, and that each of us eventually returns to the original, universal state.

Given the intimate connection between humans and butterflies throughout, the movement also illustrates the short and frantic nature of human life before “ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

Through 4 repeats, the canon cycles through several modal variations before returning to the original C major figure, perhaps signifying that there are only slight variations in each life, and that each of us eventually returns to the original, universal state.

Given the intimate connection between humans and butterflies throughout, the movement also illustrates the short and frantic nature of human life before “ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

5. Haiku anon.

It has no voice,

the butterfly, whose dream of flowers

I fain would hear

the butterfly, whose dream of flowers

I fain would hear

After 12 lives quickly flit by in movement 4, we return to a moment of calm in movement 5.

However, it is a disorienting calm.

For the first time in the piece, we hear an extended minor chord. Only the first sopranos sing text – gone are the shadowing effects and duets showing the connection between human and butterfly.

Instead, we experience a moment of solitary uncertainty…the butterfly can’t be heard, all we hear is our own voice, and even it is confusing.

Tavener’s four different variations of a 4-note melody in 5-beat meter create a feeling of disorienting and foreboding bewilderment.

However, it is a disorienting calm.

For the first time in the piece, we hear an extended minor chord. Only the first sopranos sing text – gone are the shadowing effects and duets showing the connection between human and butterfly.

Instead, we experience a moment of solitary uncertainty…the butterfly can’t be heard, all we hear is our own voice, and even it is confusing.

Tavener’s four different variations of a 4-note melody in 5-beat meter create a feeling of disorienting and foreboding bewilderment.

6. The Butterfly by Pavel Friedmann

He was the last. Truly the last.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

Like the sun’s tear shattered on stone.

That was his true colour.

And how easily he climbed, and how high.

Certainly, climbing, he wanted

To kiss the last of my world.

I have been here seven weeks. Ghettoized.

Who loved me found me,

Daisies call to me,

And the branches also of the white chestnut in my yard.

But I haven’t seen a butterfly here.

The last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

Like the sun’s tear shattered on stone.

That was his true colour.

And how easily he climbed, and how high.

Certainly, climbing, he wanted

To kiss the last of my world.

I have been here seven weeks. Ghettoized.

Who loved me found me,

Daisies call to me,

And the branches also of the white chestnut in my yard.

But I haven’t seen a butterfly here.

The last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

In a piece where each movement is a dream, and where many are quite surreal, this is a vivid nightmare. It literally bursts forth out of the quiet, foreboding loneliness of movement 5.

And not only is it loud, it is jarringly dissonant and incredibly extreme. If the opening sounds like a scream to you, that is not a mistake.

The text itself is by far the most direct and vivid of the set, not written by an ancient Eastern philosopher, but by 21-year old Pavel Friedman in a concentration camp in 1942. Friedman was later deported to Auschwitz, where he died in 1944.

In a piece where the connection between butterfly and man symbolizes a oneness with nature and a universal soul, this poem illustrates a time when that connection was lost in a place utterly devoid of humanity and spirituality.

And not only is it loud, it is jarringly dissonant and incredibly extreme. If the opening sounds like a scream to you, that is not a mistake.

The text itself is by far the most direct and vivid of the set, not written by an ancient Eastern philosopher, but by 21-year old Pavel Friedman in a concentration camp in 1942. Friedman was later deported to Auschwitz, where he died in 1944.

In a piece where the connection between butterfly and man symbolizes a oneness with nature and a universal soul, this poem illustrates a time when that connection was lost in a place utterly devoid of humanity and spirituality.

7. Butterfly Song from Acoman Indian

Butterfly, butterfly, butterfly, butterfly.

Oh, look, see it hovering among the flowers,

It is like a baby trying to walk and not

knowing how to go.

The clouds sprinkle down the rain.

Oh, look, see it hovering among the flowers,

It is like a baby trying to walk and not

knowing how to go.

The clouds sprinkle down the rain.

After the vivid nightmare illustrating a state of separation with the metaphorical butterfly, Tavener offers perhaps his most stunning movement. A simple solo line hovering around the home key of G (the key of the butterfly?) brings to life a solitary and beautiful butterfly hovering in a garden. The Native American text brings back the connection between man and butterfly and also recalls the beauty and simplicity of childhood. To me, it feels like a flashback to our earliest and happiest childhood memories.

8. Butterfly Dreams based on Chuang Tse

After three movements of man and butterfly separated, Tavener closes with a recapitulation of his first movement. The music is a carbon copy of the first - a recurring dream. After 13 minutes of a highly volatile dream state, we seem to relax back into REM, and the two versions of ourselves become closer to one.

I believe

Otche Nash, Nicolai Kedrov

After the extended dream state of Butterfly Dreams, our protagonist awakes as we turn to a moment of utter homophony in Kedrov’s simple setting of the most recited of Christian prayers, the Our Father.

I believe that for many people nearing the end of life, a moment of familiar prayer must be profoundly comforting as a psychological and emotional preparation for what is to come.

The story of this simple piece makes it even more meaningful at this moment in the album:

The son of a priest, and later in life a professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Nikolai Kedrov founded a successful vocal quartet in early twentieth-century Russia that toured Europe performing Russian folk songs, ballads, and liturgical music. After the Revolution of 1917, Kedrov fled to Germany and then later to France, where he re-established his quartet, and focused it more exclusively on Russian Orthodox music. In exile, the quartet continued to perform liturgical chants of the Russian Church, including his contemplatively beautiful Otche Nash.

I believe that for many people nearing the end of life, a moment of familiar prayer must be profoundly comforting as a psychological and emotional preparation for what is to come.

The story of this simple piece makes it even more meaningful at this moment in the album:

The son of a priest, and later in life a professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Nikolai Kedrov founded a successful vocal quartet in early twentieth-century Russia that toured Europe performing Russian folk songs, ballads, and liturgical music. After the Revolution of 1917, Kedrov fled to Germany and then later to France, where he re-established his quartet, and focused it more exclusively on Russian Orthodox music. In exile, the quartet continued to perform liturgical chants of the Russian Church, including his contemplatively beautiful Otche Nash.

I can imagine two very valid and different interpretations of this piece:

- Performing it as it would be performed in its liturgical home – a Russian cathedral. With a large choir, octavists (very low basses!) doubling the low bass part, suitably slow, rich, and reverent. This may be how Kedrov envisioned when he composed it.

- Performing it as a quartet might perform it, thinking of Kedrov’s life and circumstances after the revolution, and how it was performed by his quartet. This interpretation likely carries a slightly faster tempo, may be more limber to allow more breaths, and may be less likely to have an octavist. Perhaps it is more contemplative and imbued with an emotional sense of longing for home.

Given that the piece was composed in 1922 after Kedrov fled Russia, I gravitate towards the latter interpretation. When we perform this piece, I think we must think of ourselves as exiles, uncertain if we will ever see our home again...

A not-so-secret secret about me is that before plunging back into choral music, I used to be a management consultant.

Yeah, one of these:

Yeah, one of these:

What did that mean? Well, it meant that I used to spend an inordinate amount of time using odd business lingo that attempted (and failed) to make very dry, inactive, boring tasks into things that sound strangely active. Phrases like:

"What levers can we pull to really move the needle on this?" (translation: "let's change some of these somewhat arbitrary assumptions in this excel file")

"I've been putting out fires all day" (translation: "I got 10 emails this morning")

"Let's double-click on that idea" (translation: "I'm going to make this conference call even longer, feel free to stay on mute")

I'm happy to have left that part of my old job behind.

But, another part of that job was to make charts.

Lots of charts.

Many many many charts.

If you had asked me "should we say this with 20 words or with 10 charts?", my answer would have been: "I think you are missing a third option - maybe we should try 20 charts!"

And you know what? The sad thing is that I grew to kind of like that.

No, let's be really honest, I love it. I really think charts have the potential to display information in a way that both (a) reveals hidden patterns, and (b) displays knowledge in a way that it imprints on the brain in a very visual way.

Queue the segue to ... charts in choral music!

(seamless transition?)

It may be that choral music has been fortunate NOT to have a former consultant attack score analysis. If that is the case, I apologize for the rest of this post.

But, a few Skylarks have encouraged me to share some of the insanity that I've shown in our rehearsals and retreats. Given our upcoming foray into the Rachmaninoff Vespers, it seems like a fun time.

I'll offer three little snapshots in this post.

Here we go:

"What levers can we pull to really move the needle on this?" (translation: "let's change some of these somewhat arbitrary assumptions in this excel file")

"I've been putting out fires all day" (translation: "I got 10 emails this morning")

"Let's double-click on that idea" (translation: "I'm going to make this conference call even longer, feel free to stay on mute")

I'm happy to have left that part of my old job behind.

But, another part of that job was to make charts.

Lots of charts.

Many many many charts.

If you had asked me "should we say this with 20 words or with 10 charts?", my answer would have been: "I think you are missing a third option - maybe we should try 20 charts!"

And you know what? The sad thing is that I grew to kind of like that.

No, let's be really honest, I love it. I really think charts have the potential to display information in a way that both (a) reveals hidden patterns, and (b) displays knowledge in a way that it imprints on the brain in a very visual way.

Queue the segue to ... charts in choral music!

(seamless transition?)

It may be that choral music has been fortunate NOT to have a former consultant attack score analysis. If that is the case, I apologize for the rest of this post.

But, a few Skylarks have encouraged me to share some of the insanity that I've shown in our rehearsals and retreats. Given our upcoming foray into the Rachmaninoff Vespers, it seems like a fun time.

I'll offer three little snapshots in this post.

Here we go:

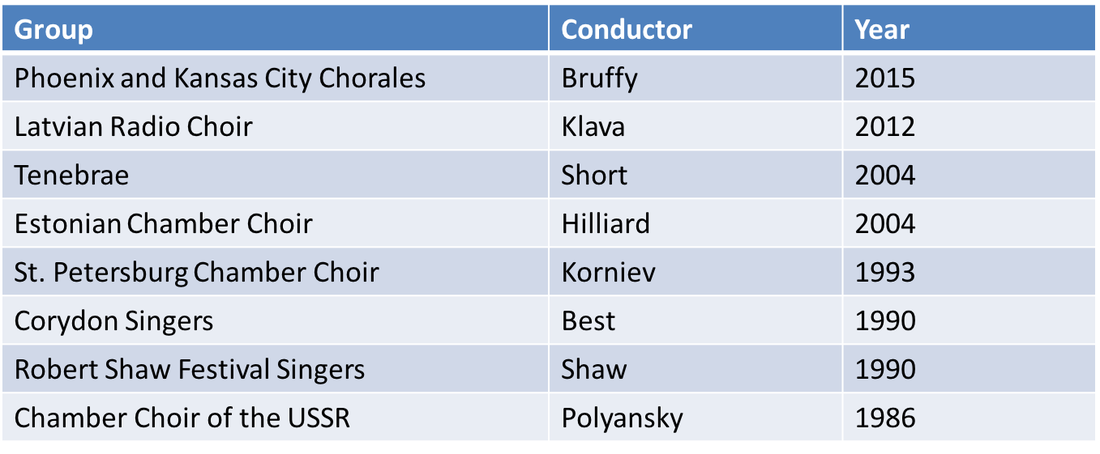

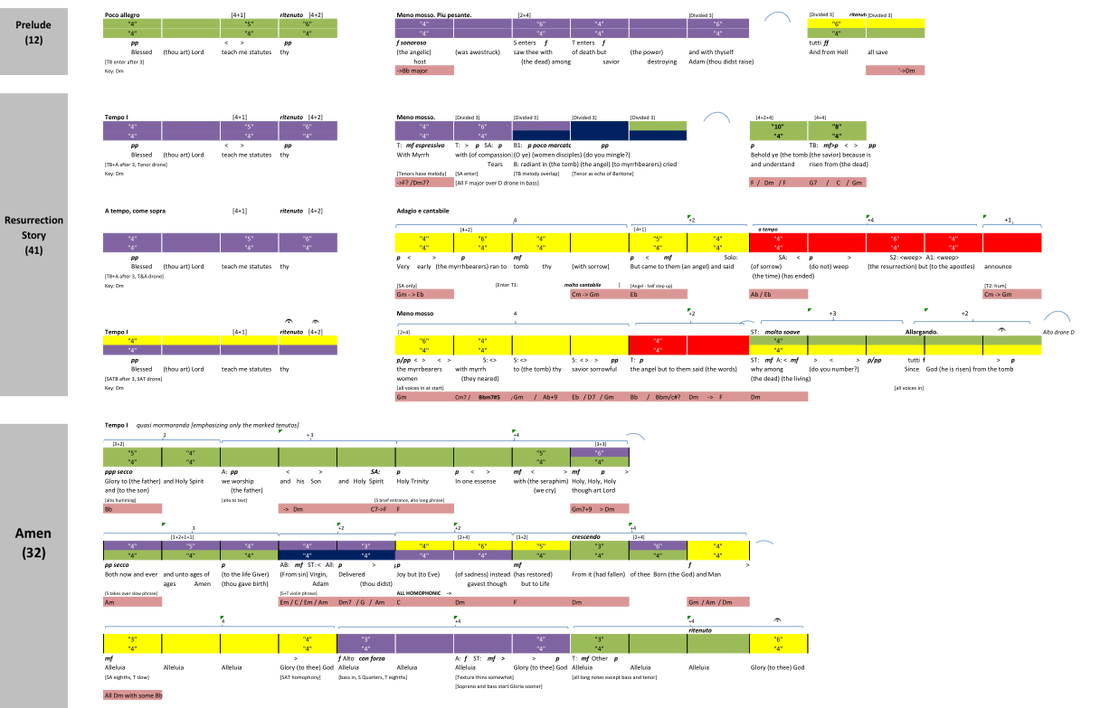

(1) Tempi Time

I'm now almost totally obsessed with tempo. When you are fortunate enough to work with the quality of musicians in Skylark, it frankly is one of the few things you bring to the table as a conductor that matters a LOT.

A lot of great choirs have performed the Rachmaninoff Vespers (yeah, I know it's the All-Night Vigil, but Vespers is easier to type so we'll go with it).

Let's just take 8 very good recordings - I'm sure there are other great ones), but here's a start:

A lot of great choirs have performed the Rachmaninoff Vespers (yeah, I know it's the All-Night Vigil, but Vespers is easier to type so we'll go with it).

Let's just take 8 very good recordings - I'm sure there are other great ones), but here's a start:

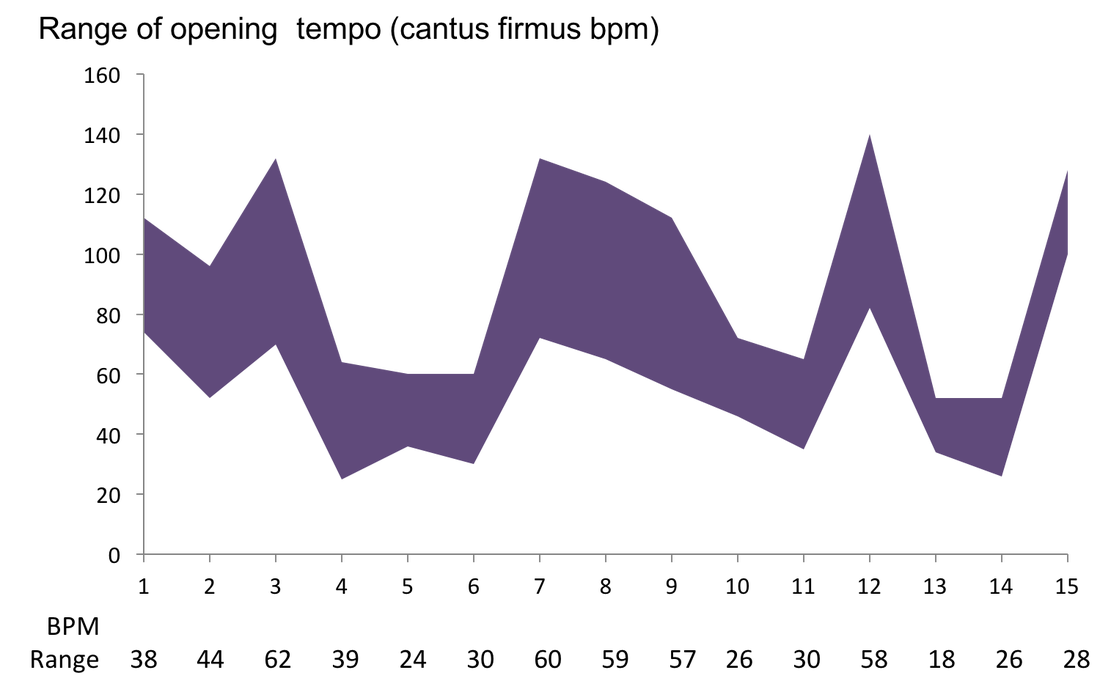

I took my handy-dandy vintage tempo watch and recorded the opening tempo of each movement across these 8 recordings (ignoring for now tempo changes within movements). If you take the 15 movements along the x axis, and graph the range of the 8 performances of each movement, you see this picture:

Wow!

Ok, sure, for some of the movements, there seems to be a tighter band, but Good Lord there is a huge range on some of those movements. Look at Movement 9 - the slowest recording of the 8 starts that movement at about 55 beats per minute, while the fastest breaks out of the gate at a brisk 112, more than TWICE as fast.

So, lesson #1 - the choices we make are enormously important and have a huge impact on the arc and length of the piece. If we followed the slow end of this graph, we'd clock the piece at around 70 minutes, while the high end gets us headed out to beers after just 50! I have some ideas on which end the Skylarks would vote for.

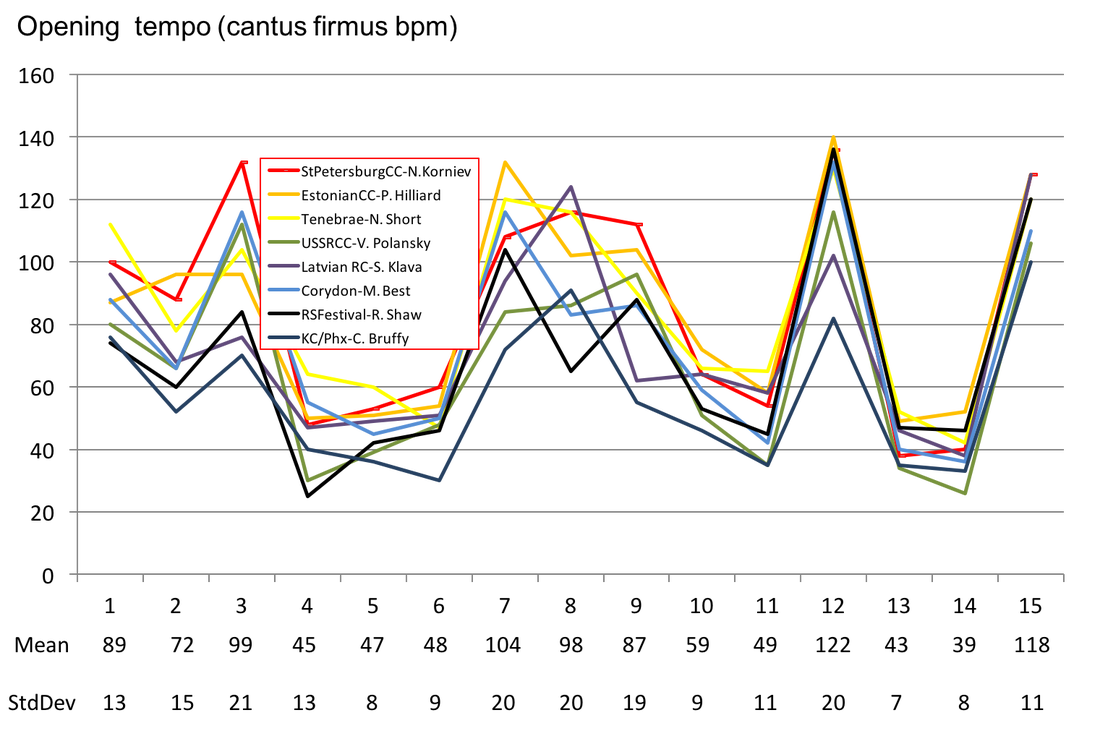

Ok, you may wonder who is who in the anonymous chart above. It looks a bit like spaghetti, but here it is:

Ok, sure, for some of the movements, there seems to be a tighter band, but Good Lord there is a huge range on some of those movements. Look at Movement 9 - the slowest recording of the 8 starts that movement at about 55 beats per minute, while the fastest breaks out of the gate at a brisk 112, more than TWICE as fast.

So, lesson #1 - the choices we make are enormously important and have a huge impact on the arc and length of the piece. If we followed the slow end of this graph, we'd clock the piece at around 70 minutes, while the high end gets us headed out to beers after just 50! I have some ideas on which end the Skylarks would vote for.

Ok, you may wonder who is who in the anonymous chart above. It looks a bit like spaghetti, but here it is:

Ok, so that was a little hard to read! But I did notice one thing by focusing a bit.

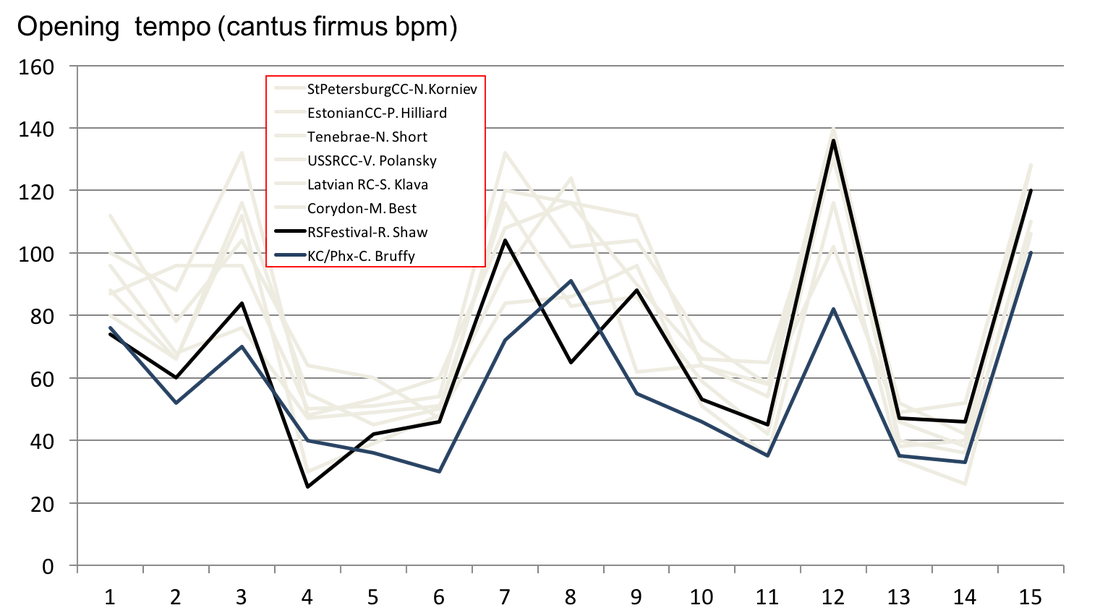

Look at the two American choirs:

Look at the two American choirs:

I found this absolutely fascinating. This is not aimed as a critique of either Mr. Shaw or Mr. Bruffy - I admire both of their work deeply. But it is important to recognize that their recordings take a very expansive view of the work relative to some other great choirs and recordings from Europe and Russia. This told me as an American (who grew up with the Shaw recording) that I could be very susceptible to starting my study of the score with a particular form of bias already bouncing around in my head.

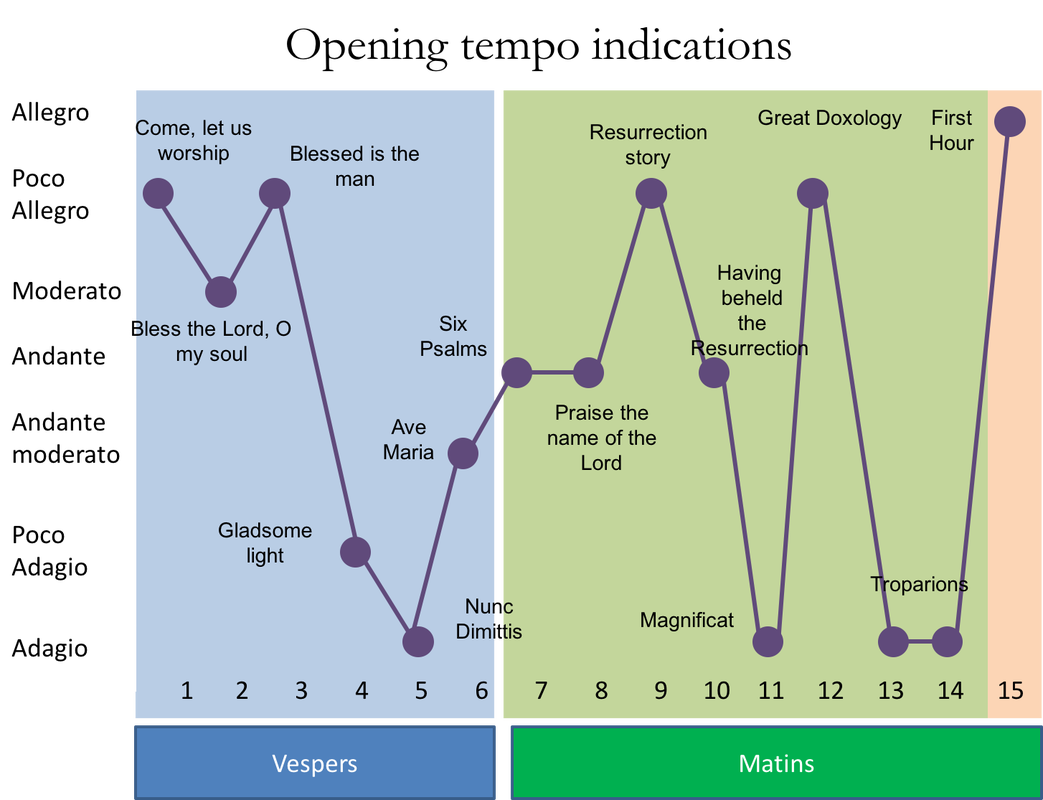

Another thing I noticed is that none of the recordings really follows this arc (This chart just graphs the opening tempo indications for each movement on a relative basis):

Another thing I noticed is that none of the recordings really follows this arc (This chart just graphs the opening tempo indications for each movement on a relative basis):

What did I notice when comparing this to the major interpretations above?

- Movement 2 is often sung very slowly, it seems to me

- A lot of interpretations seem to "bottom out" their tempo in movement 4, and then get stuck there through movement 6. However, the composer indicates that #5 should be the slowest point in the first half of the work, and that #6 should start to animate things again

- Similarly, it seems like a lot of choirs "peak too soon" in movements 7 and 8, and then lose tempo energy in movement 9, which seems to cheat the arc of the work overall

(Caveats for the truly nerdy: these tempo markings are Mussica Russica's Italian versions of the original Russian, so there may be some debate here, but I'm going to take it as a good start; also, there's some question as to whether the indication applies to the half note or quarter note - I did my best to guess for these charts).

Ok, that's a lot! On to #2...

- Movement 2 is often sung very slowly, it seems to me

- A lot of interpretations seem to "bottom out" their tempo in movement 4, and then get stuck there through movement 6. However, the composer indicates that #5 should be the slowest point in the first half of the work, and that #6 should start to animate things again

- Similarly, it seems like a lot of choirs "peak too soon" in movements 7 and 8, and then lose tempo energy in movement 9, which seems to cheat the arc of the work overall

(Caveats for the truly nerdy: these tempo markings are Mussica Russica's Italian versions of the original Russian, so there may be some debate here, but I'm going to take it as a good start; also, there's some question as to whether the indication applies to the half note or quarter note - I did my best to guess for these charts).

Ok, that's a lot! On to #2...

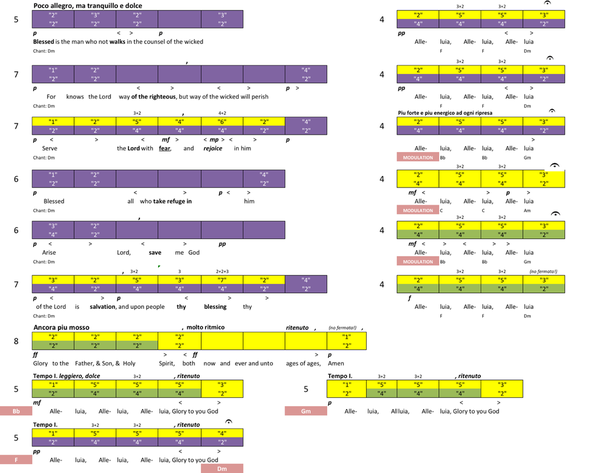

(2) Cantus statisticus

This piece is incredibly chant-driven. All of the movements have a cantus firmus (some from the Russian liturgical tradition, some written by Rachmaninoff as "conscious counterfeits").

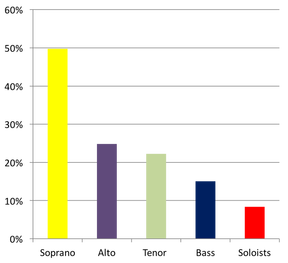

So, who has the chant the most? A simple graph helps us see this right away:

So, who has the chant the most? A simple graph helps us see this right away:

The Sopranos have the primary chant a LOT. Altos and tenors some, Bass less so, and occasionally soloists. (Nerdy Q: Why does this equal more than 100%? Nerdy A: Because sometimes the cantus firmus is doubled)

That's not terribly earth shattering, but it is interesting data. Sopranos, don't let it go to your heads. It probably means that when the basses do have the cantus firmus, it's pretty important.

But what I found more interesting was applying this to a visualization of the piece as a whole. What if we envisioned every measure of each movement as a "color" based on who has the melody (based on the colors above)? (if it is doubled, it would be two colors)

What if we then laid out the entire piece like this?

Well....

That's not terribly earth shattering, but it is interesting data. Sopranos, don't let it go to your heads. It probably means that when the basses do have the cantus firmus, it's pretty important.

But what I found more interesting was applying this to a visualization of the piece as a whole. What if we envisioned every measure of each movement as a "color" based on who has the melody (based on the colors above)? (if it is doubled, it would be two colors)

What if we then laid out the entire piece like this?

Well....

Ok, that's a lot to take in.

But I love this picture as it starts to show the macro structure of the piece overall, and also shows incredible variation in the compositional complexity between different movements.

Look at the symmetry between #1 and #15: almost exactly the same length, both dominated by soprano and tenor (in #1, they double the chant for the whole movement, in the last, they trade).

Look at the incredible uniformity of the structure in movement 11! Basses singing verses that get longer and longer (trivia: the last phrase ends with the word "forever") separated by a repeated soprano-driven refrain.

By contrast, look how complex movements 9 and 12 are (these are where Rachmaninoff really shows off his orchestral compositional chops, as pointed out by Peter Jermihov)

I like this chart a lot, as I think it sets up this last teaser...

But I love this picture as it starts to show the macro structure of the piece overall, and also shows incredible variation in the compositional complexity between different movements.

Look at the symmetry between #1 and #15: almost exactly the same length, both dominated by soprano and tenor (in #1, they double the chant for the whole movement, in the last, they trade).

Look at the incredible uniformity of the structure in movement 11! Basses singing verses that get longer and longer (trivia: the last phrase ends with the word "forever") separated by a repeated soprano-driven refrain.

By contrast, look how complex movements 9 and 12 are (these are where Rachmaninoff really shows off his orchestral compositional chops, as pointed out by Peter Jermihov)

I like this chart a lot, as I think it sets up this last teaser...

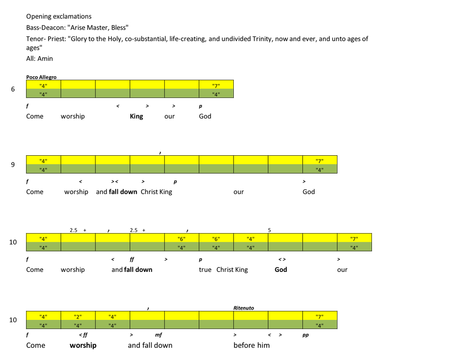

(3) Graphico-structural analysis (I made that up)

So, this post is almost over, and this last bit will just be a few snapshots. But that last graph really got me thinking about how to visualize musical phrase structure spatially and with colors.

I created a little makeshift system in excel to display phrases spatially, using the color system above. I also notated text, dynamics, and key musical notes in the score, as well as some very rough harmonic analysis when that seemed critical.

What resulted was an "aerial view" of each movement. I think they show the incredible contrast in the structure of the various movements.

Here are a few.

Movement 1: pretty straightforward

Movement 3: Okay, a little busier, but still a clear pattern - verses, responses, and a big coda

Movement 9: Yikes!

I'll end this journey into esoterica on that note.

If anyone actually read this whole post (Bueller? Bueller?) and is interested in chatting or hearing more, come to my pre-concert talk at Spivey Hall before our concert next week!

If anyone actually read this whole post (Bueller? Bueller?) and is interested in chatting or hearing more, come to my pre-concert talk at Spivey Hall before our concert next week!

Tackling a piece like the Rachmaninoff All-Night Vigil that has been so capably performed and recorded by so many world-class ensembles requires a healthy dose of both humility and insanity.

I never would have imagined programming the piece so early in Skylark's life had it not played such a pivotal role in my own in late 2014.

In this, my first-ever blog post, I'd like to share the story that inspired our Spivey performance...

(Written November 20, 2014)

Carolyn and I have always loved the Robert Shaw recording of the Rachmaninoff Vespers. It was a favorite of her family for drives to Deer Isle, Maine when she was a child, and I've always played it when I wanted to just sit and "be" surrounded by something beautiful.

Yesterday, it took on a whole new meaning for our family.

We had our portable speaker with us in the delivery room at Piedmont Hospital yesterday, and at some point during the day, we clicked over to the Shaw Vespers recording on the Ipod, looking for something calming.

The delivery did not go "as planned." (I'm sure they never do.) After ten hours of stressful rigamarole, there came a time when something drastic needed to be done to help dear baby and dear Carolyn finish the task at hand. Suddenly, as if out of nowhere, there were ten people in our room, and the order was "We're going to the OR, stat!" The whirlwind of activity left the room in under a minute. I gave Carolyn a quick kiss goodbye and watched them leave.

Suddenly, I was in the room alone with a nurse-in-training, who helped me gather our belongings to move to a recovery waiting area.

The sense of emptiness in the room was palpable, my sense of disoriented confusion and worry at its highest ever.

On the counter in the corner, the beautiful choir in France continued to sing.

After being told that I would not be able to go with Carolyn, because the procedure was an emergency and needed to happen so quickly that she would require general anesthesia, I gathered the suitcases, the shoes, the snacks, the clothes, and the speaker, and walked some distance I'll never recall to a descriptionless recovery room where I was to wait.

The speaker kept singing on the walk.

When we arrived in the room, my companion asked someone "Do we need to turn this off?"

"No, it's fine, leave it on," was the response.

It was only about 15 minutes, but it was the scariest time of my life. A non-praying man uttered some prayers for his wife and child. And the choir sang on.

Little Harry was born at 7:17 p.m. When a nurse came to see me at 7:19 or so, the sixth movement, the Bogorditse Dyevo, which is a setting of Ave Maria that was sung at our wedding seven years ago, was coming to a close. It's a little over three minutes long. I surmised then that the Ave Maria, a hymn to the miracle of birth (although a virgin one!) was playing at the moment that Harry and mom were rescued from their ordeal.

I pressed pause to talk to the nurses who told me all was well, and who then darted to the operating room to take pictures of little Harry.

After a few frantic sobs, I regained my composure and pressed play again. The seventh movement started. Slava v vyshnikh Bogu..."Glory to God on High, and on earth peace, goodwill towards men...open thou my lips, O Lord, and my mouth shall show forth thy praise.”Ten minutes later, they brought Harry to our room. They ran his first tests, gave him a bath, and pronounced him in perfect health. I watched alone, as Carolyn was still asleep from the surgery.

After his bath, they gave Harry an adorable blanket and a little hat, and handed him to me.